By Terry Beckenbaugh, US Army Command and General Staff College

"You’ve heard of Jeb Stuart’s ride around McClellan? Hell, brother, Shelby rode around MISSOURI!” – Missouri Confederate Cavalry boast.

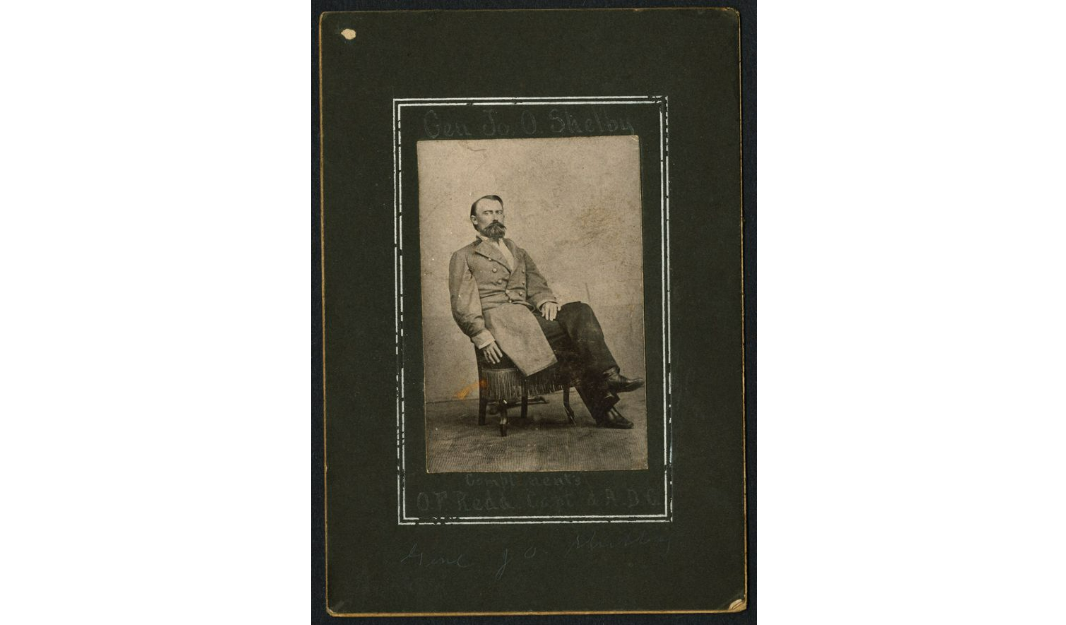

Shelby’s Raid is one of the great unsung raids of the American Civil War. The raid lasted over 40 days and covered more than 800 miles of territory in west central and northwest Arkansas and southwest and west central Missouri in the autumn of 1863. While spectacular, the raid had little lasting result on the course and conduct of the war in Missouri or in other theaters. It did earn Joseph O. “Jo” Shelby a general’s star and cemented his reputation as one of the Civil War’s most daring cavalry commanders.

The Confederacy faced a grim strategic situation in the autumn of 1863. In the Eastern Theater, Robert E. Lee and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia suffered an epic defeat at the Battle of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania (July 1-3, 1863), forcing Lee to retreat back across the Potomac River into Virginia. While famous, the defeat was not crippling to the Army of Northern Virginia, as it continued fighting for almost two more years. However, the defeat was viewed by many as a turning point. Things were worse for the rebels the further west one traveled.

The federals opened up the Mississippi River in July when the Confederate fortresses at Vicksburg, Mississippi, and Port Hudson, Louisiana, fell. Vicksburg was the key, as it lay in a very strong position high above a bend in the Mississippi River. Union Major General Ulysses S. Grant captured Vicksburg on July 4, and Major General Nathaniel P. Banks accepted the surrender of Port Hudson, Louisiana, on July 9. Port Hudson’s fall opened up the Mississippi River from source to mouth, but the news from the Trans-Mississippi for the rebels was not any better.

The entire year of 1863 proved disastrous for the Confederates in Arkansas. It started before the New Year when a Confederate force under Major General Thomas C. Hindman tried to reverse the verdict of the Battle of Pea Ridge and give the rebels a foothold in Missouri in early December 1862. Hindman was defeated on December 7, at the Battle of Prairie Grove, Arkansas, and forced to retreat back to Fort Smith, Arkansas. At the other end of the state, a federal Army-Navy force captured Fort Hindman on January 11, 1863. The fort prevented the Union Navy from going up the Arkansas River into the heart of the state, but with Fort Hindman in federal hands, the state’s interior lay wide open to invasion. The Confederates were anything but passive and tried to halt the Union’s momentum, but that, too, failed.

The Confederates’ best chance of turning the situation to their advantage came when a large rebel force attacked the Union enclave of Helena, Arkansas, on the Mississippi River on July 4. Even though the Confederates, led by Lieutenant General Theophilus Holmes, held a close to two-to-one advantage over the federal garrison inside Helena, the rebels were dealt a sharp defeat. Not only did the Confederates fail to take Helena, but all of central Arkansas lay open to federal invasion.

The Union strengthened its grip on the state when a force under Major General Frederick Steele captured Little Rock on September 10, 1863. With the fall of the state capital, the federals held the Arkansas River line, from Fort Smith, through Little Rock, down to Arkansas Post in the southeast corner of the state. Before the disaster at Helena and the fall of Little Rock, Shelby and his “Iron Brigade” participated in two Confederate raids into Missouri, led by Brigadier General John S. Marmaduke. Desperate for any success in the region, Marmaduke’s raids were attempts to give Missouri rebels encouragement. Both of Marmaduke’s Raids, the first in late 1862 and early 1863, and the second in the spring of 1863, were failures. They caused a lot of damage and hardship to the civilian population, but were poorly planned and sloppily executed and did little damage to the federals in Missouri. Shelby believed he could do better, as he saw first-hand the flaws in Marmaduke’s execution of those raids. It was against this backdrop of Confederate defeats and demoralization that Shelby decided to attempt his own daring raid deep into Missouri.

Shelby, then a colonel, proposed the Great Raid to Missouri Governor-in-exile Thomas Reynolds. Not only would he try to prove that the federals’ grip on Missouri was tenuous, but he had a full agenda of goals. He wanted to recruit more Missourians for his command and to rally the flagging spirits of pro-Confederate Missourians. Shelby wanted to divert federal troops to Missouri and keep them from reinforcing the Union campaign to capture Chattanooga, Tennessee. Finally, Governor Reynolds promised Shelby that if he successfully executed the raid, he would receive a promotion to brigadier general.

Shelby wasted no time in launching his raid. He received final approval from Major General Sterling Price on August 21, and he and his command of 600-750 men (sources vary) left Arkadelphia, Arkansas, the following morning. The ensuing raid was not for the faint of heart, as Shelby drove his men and their mounts to exhaustion. He needed to do so to make sure his men were not captured by superior federal forces in Missouri.

Shelby’s force made it to the Arkansas River, which it crossed on September 27 without alerting the federal authorities. He crossed into Missouri near Pineville and picked up more men to raise the size of his force to over 1,000. Shelby wasted little time as he attacked a federal force at Neosho, Missouri, and forced its surrender on October 2. This gave his command a significant amount of supplies, ammunition, weapons, and roughly 400 more horses. The following day, Shelby attacked a federal garrison in Greenfield, Missouri, where he forced the federals to surrender and burned the local courthouse. By this point the federal commander of the Department of the Missouri, Major General John Schofield, could no longer ignore Shelby’s presence and alerted Union military authorities in Missouri to start converging on the rebel raiders.

Shelby and his men continued their rampage. They attacked local Missouri militia at Humansville on October 6 and captured 30 wagons filled with commissary supplies. The following day, Shelby attacked the federal garrison at Warsaw, Missouri, where he captured 30 wagonloads of arms and food, as well as 10 Union prisoners. While Shelby’s rampages continued, the federals converged on Shelby’s raiders from three directions. Union Brigadier General Thomas Ewing, commander of the Border District of Missouri (the Missouri-Kansas Border) moved in from the west while Brigadier General Egbert Brown, commander of the District of Central Missouri, closed in from Boonville to the southeast while Lieutenant-Colonel Bazel Lazear advanced from the east. The federals had a combined force of roughly 2,800 men. Shelby appeared to be in a trap.

View Shelby's Raid in a larger map

Lazear reached Shelby first and skirmished with his raiders on October 11. This alerted the wily Confederate that federal forces were not only nearby, but in larger numbers and deployed to prevent his escape. Shelby determined to withdraw toward Marshall, but laid an ambush of Lazear at Dug Ford on the Lamine River. The sharp fight slowed Lazear, but did not stop his pursuit. Shelby made it to and through Marshall, and found that his escape routes were cut off. He had no choice but to fight.

Shelby fought the largest engagement of the raid on October 13 at the Battle of Marshall. Shelby decided to try to fight his way out of the federal trap. He attacked Lazear, but the federal force refused to budge. While Shelby was engaged with Lazear, Brigadier General Egbert Brown brought up a Union force in Shelby’s rear and began pressing the Confederate raiders. With his force caught in a vise, Shelby decided he needed to attempt a breakout of the federal encirclement. At just the moment Shelby’s men were saddling up to fight their way out, one of Lazear’s subordinates, Major George W. Kelly of the Fourth Missouri State Militia Cavalry, charged Shelby’s force, splitting it in two. One element of Shelby’s force, roughly 600 men, broke out to the northwest, while the other element, under Colonel David Hunter with around 400 men, managed to escape to the east. Casualties were surprisingly light on both sides, with fewer than 10 total. That low number is probably attributable to the heavy brush where most of the fighting occurred.

Throughout the night of October 13-14, Shelby kept his men moving toward Waverly. They reached there by dawn, still closely pursued by the federals. Upon reaching Waverly, Shelby decided that he had to try to get back to Arkansas. The Unionist pursuit continued as Shelby drove southwest toward Carthage, Missouri, which he and his men reached on October 19. The following day, Shelby’s raiders crossed the state line into Arkansas, after reuniting with the rest of his forces along the Osage River. Shelby’s command crossed the Arkansas River after some more skirmishing with the federals, and his exhausted, worn-out men arrived in Washington, Arkansas, on November 3. Thus ended one of the longest and most daring raids of the entire Civil War.

While the raid makes compelling reading, in terms of its military effects it left a mixed record. Shelby did indeed receive his promotion to brigadier general after the raid. Shelby, who was seriously wounded in the arm during the disastrous Battle of Helena several months earlier, showed undisputed courage, leadership, and tremendous tactical instincts. To have escaped the trap at Marshall was a mixture of luck, audacity, and leadership. Shelby’s reputation received a well-deserved boost. But Major John Newman Edwards, who wrote Shelby’s reports, certainly exaggerated when he listed their accomplishments of 1,500 miles traveled, 600 killed and wounded, and 500 captured and paroled. The raiders destroyed a significant amount of property, but their prime purpose—to divert federal troops to Missouri—failed. The troops that chased Shelby across the state were generally Missouri militia – units that would only have left the state under the direst circumstances. Furthermore, unbeknownst to Shelby, the federals and Confederates fought the second bloodiest battle of the war in extreme northwest Georgia, the Battle of Chickamauga, on September 19-20, while the raid was in progress. The battle was a startling rebel victory, but it did not lead to the Unionist abandonment of Chattanooga, Tennessee, a vital railroad hub.

Ultimately, the raid failed in its strategic goals and caused a great deal of suffering for Missourians of all stripes with the property damage and the number of horses and amount of food Shelby’s men stole. The state had by that time already suffered from over two years of guerrilla warfare that devastated the countryside. Shelby’s raid only added to that suffering.

Suggested Reading:

Feild, Patrick. “Thrilling but Pointless: General “JO” Shelby’s 1863 Cavalry Raid.” Master of Military Arts Thesis, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, U. S. Army Command and General Staff College, 2013.

Gerteis, Louis. The Civil War in Missouri: A Military History. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2012.

McLachlan, Sean. Ride Around Missouri: Shelby’s Great Raid 1863. Oxford, United Kingdom: Osprey Publishing, Ltd., 2011.

O’Flaherty, Daniel. General Jo Shelby: Undefeated Rebel. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2000. Originally published in 1954.

Oates, Stephen. Confederate Cavalry West of the River. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1992. Originally published in 1961.

Cite This Page:

Beckenbaugh, Terry L.. "Shelby’s Raid" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Wednesday, July 3, 2024 - 02:57 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/encyclopedia/shelby%E2%80%99s-raid