By Terry Beckenbaugh, U. S. Air Force Command and Staff College

View A Long and Bloody Conflict (Part II) in a larger map

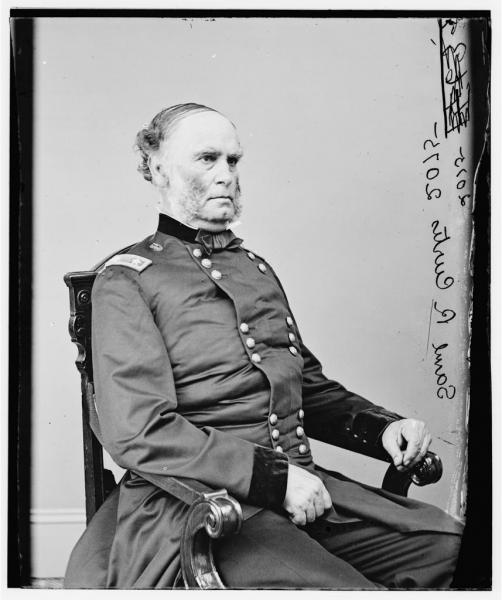

The start of 1862 witnessed the federals in their most precarious position of the war in Missouri. Sterling Price’s Missouri State Guard (MSG) controlled the interior of the state – including large sections of the strategically vital Missouri River Valley. Guerrillas ran rampant through the interior as well. It was up to the newly-installed commander of the Department of the Missouri, Major General Henry W. Halleck to restore the Union’s fortunes in the states. Halleck was not idle over the holiday season of 1861, as he instructed Brigadier General Samuel R. Curtis, commander of the recently-formed Federal Army of the Southwest, on his plans for the upcoming campaign season.

Battles of Pea Ridge and Prairie Grove

Curtis’s mission was clear: remove Confederate forces from Missouri. As long as Price and the Missouri State Guard remained in Missouri as a potential threat to St. Louis, federal forces looking to move down the Mississippi River would have to be kept near that vital city. Starting in January 1862, the federal Army of the Southwest left Rolla, marching toward Springfield. Price’s Missouri State Guard was taken by surprise, and it retreated in a disorderly manner toward the southwest corner of the state.

Price knew that the further the federals were drawn away from the railroad head at Rolla, the more vulnerable they became. Also, Price was falling back toward Confederate forces under Brigadier General Ben McCulloch in northwest Arkansas. Reuniting the two forces would give the Confederates a significant numerical advantage over Curtis, but getting Price and McCulloch to work together had previously proved impossible. Something had to change.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis tried to solve the command issues by placing Major General Earl Van Dorn in command of the combined force on January 29, 1862. Van Dorn was a West Point graduate, class of 1842, and Davis clearly hoped that Van Dorn’s professional background could reenergize the rebel war effort in the Arkansas-Missouri region. After Price’s headlong retreat into Arkansas, where the Boston Mountains allowed him to escape from Curtis’s forces, Van Dorn united Price and McCulloch’s forces into the Confederate Army of the West. After this reorganization of the Confederate forces under his command, Van Dorn decided to attack the federals while they were at the end of a very long and tenuous supply line.

Van Dorn’s plan to destroy the Unionists was bold: move around the federal force and strike it from the rear. This required almost superhuman efforts from the men in Confederate ranks. The 16,000-man Army of the West’s attempts to outflank the 10,500-man Army of the Southwest started the Battle of Pea Ridge on March 7, just east of modern-day Bentonville, Arkansas. The flanking attempts failed and the federals spoiled the rebel attacks in a day of ferocious fighting.

On the following day at Pea Ridge, the Army of the Southwest counterattacked and drove the Confederates from the field in a stunning victory. The Confederates suffered approximately 2,000 casualties (killed, wounded, and missing), while the Federals took 1,300. The rebel retreat to Fort Smith and to Van Buren, Arkansas along the Arkansas River (in early March) was brutal. To make matters worse, Van Dorn took the battered remnants of the Army of the West, including the Missouri State Guard, to the east bank of the Mississippi (too late to participate in the Battle of Shiloh, Tennessee on April 6-7, where the Union won another victory). The combination of the Confederate defeat at Pea Ridge and Van Dorn’s removal of the Army of the West essentially abandoned formal control of Missouri to federal forces for the rest of the war.

The federals attempted to consolidate their control of Missouri. Curtis took the Army of the Southwest on an epic march across southern Missouri and northern Arkansas from March to July 1862, ending up at Helena, Arkansas on the Mississippi River. For his victory at Pea Ridge, Curtis was promoted to Major General and eventually given Halleck’s post as commander of the Department of the Missouri in September.

During Curtis’s tenure, the Confederates made an attempt to reverse the verdict of Pea Ridge. Rebel Major General Thomas Hindman stepped into the vacuum created by Van Dorn’s abandonment of Arkansas and Missouri on May 31, when he ascended to command the Trans-Mississippi Department. Hindman inherited a virtually defenseless state, and, in a matter of months, he not only managed to restore Confederate forces in Arkansas, but he also raised a force to go back into Missouri. Hindman’s herculean but ruthless efforts led to the creation of the rebel First Corps of the Trans-Mississippi Army of approximately 11,000 men.

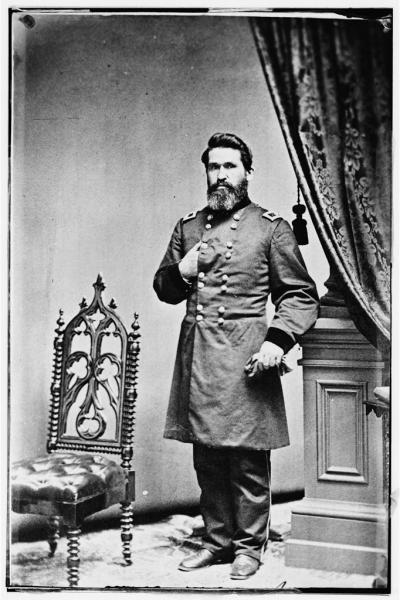

Hindman’s methods to raise this force were so draconian that he alienated many Arkansans, so Major General Theophilus Holmes was installed to head the Department over Hindman on July 30. Holmes, a West Point graduate, was well past his prime, and he allowed Hindman considerable leeway within the department. Hindman led the First Corps of the Trans-Mississippi Army up the Arkansas River to Fort Smith, then north toward the Pea Ridge battlefield in early December. He hoped to catch the 5,000-man 1st Division of the Federal Army of the Frontier, under Kansan Major General James G. Blunt, isolated from the rest of the Army of the Frontier over 135 miles away at the Wilson’s Creek battlefield outside of Springfield, Missouri.

As Hindman moved his force toward Blunt, the latter telegraphed Brigadier General Francis Herron, commander of the rest of the Army of the Frontier, to come join Blunt in Arkansas. Herron force-marched his men a remarkable 125 miles in three days to join Blunt. To prevent the federal forces from joining, Hindman moved east of Blunt and intercepted Herron at Prairie Grove, Arkansas on December 7, 1862.

In proportion to its size, the Battle of Prairie Grove was one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War. Herron gave his exhausted Union men no time to rest and sent them immediately into an attack on Hindman’s much larger force. The attack failed, but the Army of the Frontier held against a Confederate counter-attack. When it seemed that Herron’s force might be overwhelmed, Blunt arrived on the battlefield just in time to save his federal comrades.

Blunt had heard the noises of battle at Prairie Grove and marched to the sound of the guns to save Herron. Blunt immediately launched an attack with his force, which was bloodily repulsed. Hindman then launched a counter-attack against Blunt that was also stymied. During the night, Hindman’s First Corps of the Trans-Mississippi Army retreated back across the Boston Mountains to Fort Smith, after suffering 1,300 casualties. The federal Army of the Frontier had 9,200 men engaged and took 1,200 casualties. Hindman’s attempt to reverse the verdict of Pea Ridge had failed, and Missouri remained solidly under Union control.

Federal Strategy for the Trans-Mississippi

With Missouri firmly under federal control as of early 1863, Union military strategists attempted to isolate Missouri to prevent guerrillas from coming into the state or from receiving any military supplies. A state as large as Missouri was extremely difficult to pacify, so the federals concentrated on the river valleys in and around the state. With the Missouri River Valley cleared of Confederate conventional forces, the Unionists moved toward securing the Mississippi River on Missouri’s eastern border and the Arkansas River on its southern border. St. Louis was, not surprisingly, the center of Union efforts on the Mississippi River. St. Louis was a major supply hub and forward operating base for operations down the river. Most of the men and materiel supplying the guerrilla bands in Missouri came from Arkansas and Texas.

Union military strategists attempted to isolate Missouri to prevent guerrillas from coming into the state or from receiving any military supplies.

The federals determined that controlling vital points along the Arkansas River Valley would allow them to manage traffic into and out of Missouri. There were four key points along the river: Arkansas Post (where the Arkansas River empties into the Mississippi River), Little Rock, Fort Smith in Arkansas, and Fort Gibson in Indian Territory (near modern-day Muskogee, Oklahoma). The federals captured Arkansas Post on January 11, 1863, sealing off the juncture of the Arkansas and Mississippi Rivers.

On July 17, Major General Blunt led a small force of 3,000 men comprised mainly of loyal Indian and Kansas troops (including the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry) in a decisive victory over Confederate forces at the Battle of Honey Springs, Indian Territory. Blunt destroyed the Confederate depot at Honey Springs, and in the process ended Confederate large-scale operations in the region for the duration of the war. Six weeks later, Blunt’s men captured Fort Smith, securing the upper Arkansas River valley for the federals.

That left Little Rock, the capital of Arkansas, in Union hands. Union Major General Frederick Steele defeated Confederate forces under Major General Sterling Price at the Battle of Bayou Fourche on September 10 and occupied Little Rock that same evening. The capture of Little Rock by federal forces sealed Missouri’s southern border, but it was certainly not an airtight seal, as significant numbers of guerrillas still operated in Missouri and along the Missouri-Kansas border.

Although Blunt escaped, over 100 federal soldiers were killed by Quantrill’s men, many in cold blood after they had surrendered.

Quantrill’s Raiders made a mockery of the federal strategy with the Lawrence Massacre on August 21, 1863, in which they descended on a defenseless Lawrence, Kansas, and killed between 160 and 190 male civilians. Later, on October 6, Quantrill’s approximately 400 men killed some of the federals manning the earth-and-log Fort Blair, near Baxter Springs, Kansas, but they did the most damage when Major General Blunt and his escort arrived and did not realize that many of the blue jacket-wearing men were Quantrill’s. Although Blunt escaped, over 100 federal soldiers were killed by Quantrill’s men, many in cold blood after they had surrendered.

Shelby’s Great Raid

View Shelby's Raid in a larger map

Not long after Quantrill's raid on Lawrence, Confederate Colonel Joseph O. Shelby decided to test the federal cordon strategy for isolating Missouri by taking an 800-man force across the Arkansas River and deep into the state. Shelby’s raid, while costly, was successful. Shelby’s force left Arkadelphia, Arkansas on September 22, 1863, and rode deep into central Missouri, eventually crossing the Arkansas River at Clarksville on October 26.

During that interval, Shelby killed hundreds of federals and destroyed and/or confiscated a million dollars worth of supplies. He certainly made a name for himself and earned a promotion to brigadier general for his exploits. Shelby proved that the cordon around Missouri was permeable, and with a relatively small number of men he tied up thousands of federal soldiers who were desperately needed elsewhere. Shelby laid the foundation for bigger Confederate operations the following year.

Price’s Raid

View Price's Raid in a larger map

By the early autumn of 1864, the Confederacy’s prospects of winning the broader war were dwindling fast. Union Lieutenant-General Ulysses S. Grant had the rebel leader of the Army of Northern Virginia, General Robert E. Lee, trapped in a grinding siege at Petersburg, Virginia. Major General William T. Sherman’s Federal Army had recently captured Atlanta and was preparing its famous March to the Sea, or Savannah Campaign.

Against this backdrop, rebel Lieutenant General Edmund Kirby Smith, commander of all Confederate forces in the Trans-Mississippi, decided to try to conquer Missouri for the Confederacy. He placed Major General Sterling Price in charge of the 12,000-man Army of Missouri. Price enthusiastically embraced the mission and set off from Camden, Arkansas on August 28, 1864.

Price’s marauders left a trail of blood and destruction through Arkansas, Missouri, and Kansas.

For the next three-plus months, Price’s Army of Missouri rampaged throughout the interior of Missouri but failed in its goals of conquering Missouri or preventing Abraham Lincoln from gaining re-election to the presidency. Price’s marauders left a trail of blood and destruction through Arkansas, Missouri, and Kansas, before ultimately returning to Texas via Indian Territory and Arkansas in early December. They were extremely fortunate to escape annihilation at the hands of federal forces several times, most notably suffering sharp defeats at Westport (south of Kansas City, Missouri) on October 21-23 and at Mine Creek in Kansas on October 25. Price’s eviction from Missouri and Kansas essentially ended all major combat operations north of the Arkansas River in Missouri and Kansas.

Peace on the Border

The fighting in Missouri and Kansas during the Civil War did not command center stage, but it was significant nonetheless. The struggle for Missouri in the early stages of the war played a key role in the initial formulation of the Lincoln administration’s strategy. President Lincoln understood the importance of controlling the Mississippi River, and before operations could commence down the river, St. Louis (and by extension, Missouri) needed to be firmly secured on the federal side. Within this strategic context, the decisive Union victory at Pea Ridge was a critical turning point of the war in the Trans-Mississippi. Never again did the Confederacy have such a good opportunity to stake a claim to the vital state of Missouri. Defeat at Pea Ridge and Van Dorn’s abandonment of Missouri and Arkansas allowed federal expeditions down the Mississippi River to proceed.

View a clip of historian Terry Beckenbaugh discussing Civil War politics at the Kansas City Public Library.

The rebels certainly made attempts to recover Missouri. The Prairie Grove campaign and later, Price’s Raid, were efforts to reverse the setback at Pea Ridge. While the federal hold on Missouri was never seriously threatened after Pea Ridge, Missouri’s Civil War experience was by no means a tranquil one. Guerrilla bands roamed the state, as bushwhackers and jayhawkers made life miserable for civilians in large areas of both Missouri and Kansas. The widespread death, destruction, and bitterness they caused are perhaps the lasting legacy of the Civil War in Missouri and Kansas.

Suggested Reading:

Gerteis, Louis. The Civil War in Missouri: A Military History. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2012.

Lause, Mark A. Price's Lost Campaign: The 1864 Invasion of Missouri. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2011.

Monnett, Howard N. Action Before Westport 1864. Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado, 1995, revised edition. Originally published in 1964.

Shea, William L. Fields of Blood: The Prairie Grove Campaign. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Shea, William L. and Earl J. Hess. Pea Ridge: Civil War Campaign in the West. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1992.

Cite This Page:

Beckenbaugh, Terry. "A Long and Bloody Conflict: Military Operations in Missouri and Kansas, Part II" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Saturday, April 27, 2024 - 14:34 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/essay/long-and-bloody-conflict-mi...

Rights/Licensing:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License