By Claire Wolnisty, Angelo State University

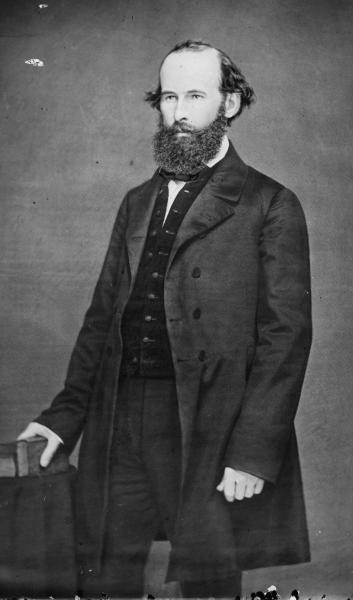

Biographical information:

- Date of birth: June 11, 1819

- Place of birth: Mendon, Massachusetts

- Claim to fame: a founder of the New England Emigrant Aid Company

- Political affiliations: Republican Party

- Date of death: April 15, 1899

- Place of death: Worcester, Massachusetts

- Buried: Hope Cemetery, Worcester, Massachusetts

Eli Thayer convinced New England businessmen to create the New England Emigrant Aid Company in response to the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of May 25, 1854. The company encouraged settlers to move to Kansas and vote it a free state under the Act’s “popular sovereignty” provisions. As Reverend Edward Everett Hale, the company’s vice-president, concluded about Thayer’s role in the Kansas settlement effort, “This emigration at that time would have been impossible but for Eli Thayer.” While Thayer fell short of fully executing his plans, he did successfully drum up enthusiasm and publicity for Free-Soil Kansas, which ultimately joined the Union as a free state.

Thayer gained a reputation for progressive views in his state of Massachusetts even before the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. In 1848, Thayer founded the Oread Collegiate Institute in Worcester, Massachusetts. Here he and his seminary staff undertook a rare task for educators of the mid-19th century: they taught female students. When Thayer was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from 1857 to 1861, he delivered a speech in the House attacking slavery on March 25, 1858. Transcendentalist and abolitionist Theodore Parker declared that “wit” and “delicate satire” defined Thayer’s address.

Thayer advocated what he called “business antislavery” when he built up the New England Emigrant Aid Company from the original Massachusetts Emigrant Company in July 1854 with the help of men such as Amos A. Lawrence, the company’s treasurer. “Sawmills and Liberty!” became Thayer’s slogan. He organized his company as a joint-stock operation and supported approximately 2,000 emigrants to Kansas Territory between the years 1854 and 1856. His goal for these emigrants was for them to “plant” saw mills and steam engines in new free labor Kansas towns such as Manhattan, Topeka, Osawatomie, and Lawrence, as well as to establish outposts against proslavery advocates in Kansas Territory. The plan was to use machinery to foster free labor which, according to Thayer’s thinking, would definitively prove how free labor was more profitable than slave labor. Thayer also believed he could both pay dividends back to his initial investors and that he could speculate in land around Kansas City.

Not all of the company’s directors supported Thayer’s ideas, however. Amos A. Lawrence, for example, viewed the company as a charity more than as a business. Lawrence considered Thayer’s focus on letting “capital be the pioneer” and his emphasis on land speculation to be “objectionable.” The company’s treasurer preferred to attend to the company’s political and philanthropic goals instead of its business ones. The company’s directors also split over their views on John Brown. While Lawrence was willing to forgive Brown for acts of violence at the Pottawatomie Massacre, Thayer quickly separated himself from Brown.

Thayer’s ability to garner support for his settlement efforts in Kansas, rather than his business sense, proved to be his most valuable asset to the emigration company.

Thayer’s ability to garner support for his settlement efforts in Kansas, rather than his business sense, proved to be his most valuable asset to the emigration company. He traveled over 6,000 miles and delivered over 700 speeches in New England while fundraising and recruiting for the company’s cause between 1854 and 1856. He employed Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune and William Cullen Bryant’s New York Evening Post in his publicity campaign. At times other directors of the company, such as J.M.S. Williams, had to ask Thayer to “sober down” his descriptions of the company because they feared that they would not be able to live up to Thayer’s glowing descriptions of settlement. Despite Thayer’s tendency to exaggerate, his fundraising efforts in New England arguably saved the company from bankruptcy in late 1855.

After Lawrence declared in May 1857 that their company met its goal of settling Free-Soil advocates in Kansas, Thayer turned his attention to other emigration plans. Thayer helped found the free labor colony of Ceredo, Virginia (now West Virginia), but John Brown’s raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, scared away many potential settlement supporters, and the outbreak of the Civil War terminated the project.

Thayer’s legacy, much like the New England Emigrant Aid Company’s legacy, is mixed. Thayer believed that his company “saved Kansas by defeating the slave power in a great and decisive contest.” Some of Thayer’s contemporaries agreed with him. Charles Sumner concluded, “The state of Kansas should be named Thayer.” But not everyone agreed with Sumner. Amos Lawrence complained that Thayer often ignored the practical elements of the company’s settlement schemes and did not visit Kansas until 1877. Thayer did not always realize that he needed to do more than merely send people to Kansas. The company members also needed to deal with daily tasks such as collecting rents and training farmers - duties that they did not always complete.

Regardless of how successful Eli Thayer and the members of the New England Emigrant Aid Company were in sending antislavery settlers to Kansas Territory, they did contribute to Kansas joining the Union as a free state in 1861. Even Amos Lawrence, who often disagreed with Thayer, remembered him positively, saying that “He never faltered in his faith, and he inspired confidence everywhere.” Company agents Charles Robinson, Samuel Pomeroy, and Martin Conway went on to become, respectively, the new state’s first governor, U.S. senator, and representative to the U.S. House of Representatives.

Suggested Reading:

Andrews, Horace, Jr. "Kansas Crusade: Eli Thayer and the New England Emigrant Aid Company," The New England Quarterly. Vol. 35, no. 4 (December, 1962): 497-514.

Harlow, Ralph Volney. "The Rise and Fall of the Kansas Aid Movement," The American Historical Review. vol. 41, no. 1 (October 1935): 1-25.

Thayer, Eli. A History of the Kansas Crusade: Its Friends and Its Foes. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1889.

Cite This Page:

Wolnisty, Claire. "Thayer, Eli" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Thursday, April 18, 2024 - 20:59 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/encyclopedia/thayer-eli