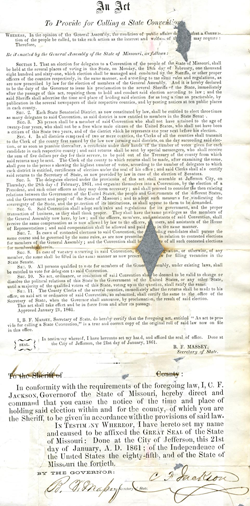

- Type: Government Document

- Date: February-March 1861

- Location: Jefferson City, Missouri

- Owning organization: Missouri State Archives

- Topics referenced: Crittenden Compromise, Abraham Lincoln

By Jason Roe, Kansas City Public Library

The Featured Document Blog places the past in your grasp by introducing a compelling item from our digital collection.

Sign up for our newsletter, This Month in the Civil War on the Western Border »

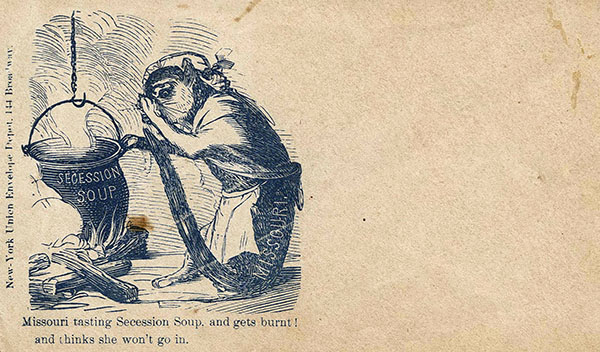

As Southern states seceded from the Union in the months leading up to the Civil War, Missouri struggled with the decision of whether to rebel and join the new Confederacy. On January 21, 1861, the state called a convention to consider the "relations between the Government of the United States ... and the Government and people of the State of Missouri; and to adopt such measures for vindicating the sovereignty of the State, and the protection of its institutions, as shall appear to them to be demanded." On February 18, voters elected an overwhelmingly pro-Union group of representatives to the convention. Despite strong Unionist sentiment, this set of resolutions from February or March of 1861 reveal that Missouri was a true border state: one that wanted to preserve slavery and yet ultimately rejected calls to abandon the Union.

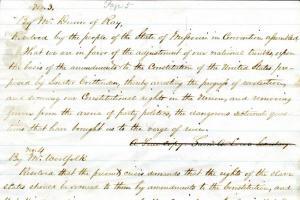

This set of resolutions encapsulated the arguments in favor of Missouri remaining in the Union, even as it maintained a strong proslavery position. The opening lines of the document suggest that the convention favored the so-called Crittenden Compromise, referring to a set of six constitutional amendments and four Congressional resolutions proposed by Senator John J. Crittenden. Intended to be palatable to both sides, the amendments would have restored the prohibition of slavery north of the 36 degree, 30 minutes line of the Missouri Compromise. Congress would be forbidden from abolishing slavery in slave states and the District of Columbia, and from interfering with the interstate slave trade. Congress would be required to compensate slave owners for escaped slaves. Most controversially, the sixth proposed amendment would forever prohibit future amendments revoking any of the six Crittenden amendments.

Supporters of the Crittenden Compromise believed it would reassure the seceded Southern states that they could remain in the Union with assurances that slavery would never be hampered by the federal government. While the proposal garnered support among representatives of Southern and border states, Republicans, including President-elect Abraham Lincoln, strongly opposed its proslavery elements.

These resolutions from the Missouri convention, however, supported the Crittenden solution. One of the resolutions stated, "there exists no adequate cause why Missouri should secede from the Union and that she will do all that she can to restore peace to the same by satisfactory compromise." Further, it held that the Constitutional union was permanent, that the federal Constitution was the "supreme law of the land and not a mere compact," and that there was no provision for states to leave the Union legally. These resolutions did uphold the concept that a revolution could be justifiable in theory, but that "in the opinion of this Convention no overt act has been committed by the General Government sufficient to justify either secession, nullification or revolution." Finally, the representatives to the convention overwhelmingly agreed in their opposition to acts of war from either side.

One poignant resolution from the batch summarized the spirit of the Missouri convention: "Resolved That we have the best government in the world and intend to keep it." By a vote of 98-1 among the representatives to the convention, Missouri became the only state to call up a convention to consider secession without actually following through with secession.

Missouri's hopes of remaining neutral proved totally unworkable as the nation careened toward Civil War. After Fort Sumter its secessionist Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson resisted President Lincoln's call to raise soldiers against the Confederacy and went so far as to raise the Missouri Volunteer Militia and later the Missouri State Guard (MSG) in defense of secessionist interests. Federal military leaders could not tolerate secessionist militias organizing within Missouri's borders, and after they instigated the disastrous "Camp Jackson Affair" in May, negotiations failed. Jackson, the MSG, and a number of likeminded state representatives abandoned Jefferson City and formed a government-in-exile as violence between the two sides escalated into full scale war with the battles of Boonville, Wilson's Creek, and Lexington in the summer of 1861.

Meanwhile, the Union set up a provisional government to manage Missouri state affairs for the duration of the war. As violence erupted, Major General John C. Frémont, commander of the Department of the West in Missouri, declared martial law and ordered the confiscation of all property—including slaves—from disloyal citizens. In order to prevent Missouri from tipping into Southern hands, though, Lincoln removed Frémont from command and reversed his orders, preserving slavery in Missouri for most of the war.

As made clear by the various resolutions from the state convention, Missouri was too much of a slaveholding border state to fit in completely with the Unionist cause. While it largely remained under federal military control throughout the war, and although the majority of its population had opposed outright secession, many Missourians continued to sympathize with the South and had little tolerance for violence instigated by either side. Meanwhile, Missouri's guerrilla "bushwhackers" harassed and challenged Union military operations in the state, its "border ruffians" continued to cross into Kansas or defend against the Unionist "jayhawkers," its citizens suffered federal reprisals (most notably General Order No. 11), and Missouri could not reconcile its internal divisions.