By Nicole Etcheson, Ball State University

In 1859, John Brown, a settler from Kansas Territory, invaded the state of Virginia with plans to raid the Harpers Ferry arsenal and incite a slave rebellion. Among his small band of insurgents were several young men who had also carried out vigilante violence in Kansas in hopes of abolishing slavery in that territory. The raid itself failed, and those who did not escape or die in the raid were later executed, including Brown himself.

In a political sense, however, the raid successfully fulfilled Brown's larger goals by igniting national divisions and helping to spark the American Civil War. The start of violence in Kansas Territory thereby led to one of the most important chapters of American history.

America's Sectional Divide

The Harpers Ferry raid sent shockwaves through the nation's political landscape, influencing the outcome of the presidential election of 1860. Northerners were reminded of the horrors of a slave system that provoked men to such drastic violence, while Southerners insisted there was no difference between radical violent abolitionists such as John Brown and more mainstream Republican candidates like Abraham Lincoln. Americans noted how Brown’s experience in Kansas had driven him to this attack.

Northerners believed proslavery harassment of Brown and other antislavery settlers, including the murder of Brown’s son, Frederick, motivated his attack on Harpers Ferry. Meanwhile, Southerners emphasized Free-Soil settlers’ violent resistance to the proslavery Kansas territorial government, connecting the Harpers Ferry raid to it as another instance of antislavery lawlessness. As abolitionist Lydia Maria Child observed, the wind sowed in Kansas, reaped a whirlwind in Virginia.

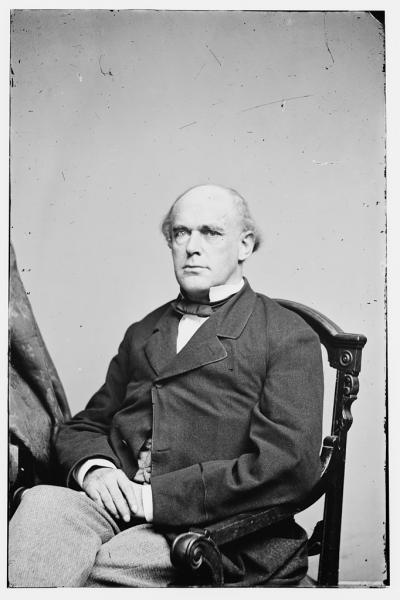

Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas never intended such a result. Douglas chaired the Senate’s committee on territories and was well aware by the early 1850s that westward expansion had stalled at the Missouri River. Under the provisions of the 1820 Missouri Compromise, the northern half of the Louisiana Purchase, west of Iowa and Missouri, was free territory. Southerners in Congress, therefore, had no interest in organizing territories there that would become free states, and legislation authorizing those territories failed. In 1854, Douglas revised the latest version of the bill, creating the territories of Kansas and Nebraska and replacing the prohibition on slavery with popular sovereignty – the right of the people, through their territorial legislatures, to decide whether to have slavery.

Popular sovereignty had a long pedigree in American politics. In 1848, Democratic presidential candidate Lewis Cass adopted popular sovereignty as his policy for dealing with slavery in the lands acquired from Mexico. Congress passed the Compromise of 1850 to settle the question of the Mexican Cession and, in his Kansas-Nebraska bill, Douglas claimed that the Utah and New Mexico provisions of that compromise were essentially precedents for popular sovereignty. By replacing the Missouri Compromise’s prohibition on slavery with popular sovereignty, he was merely repeating what Congress had done in 1850.

Many in Congress, including many of Douglas’s fellow Democrats, disagreed. Senators Salmon P. Chase and Charles Sumner were the signatories to “The Appeal of the Independent Democrats,” condemning the Kansas-Nebraska bill as “an atrocious plot” to claim the territory for “masters and slaves.” A coalition of anti-Nebraska Democrats, former Whig Party members, and anti-immigrant "Know Nothings" (of the nativist American Party) formed a fusion movement that evolved into the Republican Party, a formidable new opponent to the dominant Democrats. The Republicans opposed slavery’s expansion into the Kansas and Nebraska territories. The Kansas-Nebraska Act passed in 1854, paving the way for settlement of those territories.

Kansas Territory's "Bogus Legislature"

Events in Kansas Territory contributed to the Republican Party's growth and exacerbated the sectional conflict. Iowans crossed the border into Nebraska and voted in territorial elections, but their numbers were small and Nebraska was expected to be a free state. In Kansas, a small civil war broke out between proslavery Missourians and settlers from the free states, rooted in the flawed implementation of popular sovereignty.

Problems appeared in the first territorial election, for a delegate to Congress, in November 1854. But the disturbances that caught the nation’s attention occurred during the March 1855 election of a territorial legislature. Missourians crossed the river to vote in the territory. At polls throughout the territory, armed Missourians threatened voters and election officials from the free states. Although a territorial census had shown that there were 2,905 eligible voters in the territory, proslavery candidates were elected to the so-called "Bogus Legislature" with majorities of over 5,000 votes.

The New Englanders had embarked for the territory singing songs about making the west “the homestead of the free.”

Many of the Missourians who crossed the state line to vote did later settle in the territory. Many Northern settlers who felt deprived of their political rights abandoned Kansas, overcome by frontier hardships. Nonetheless, the proslavery victory seemed to many a blatant violation of the polls.

The newly elected territorial legislature passed a slave code for Kansas. But although Benjamin Stringfellow, publisher of a proslavery newspaper, boasted that Kansas now had slave laws as solid as any in the country, resistance was building. The small number of New Englanders in Kansas now combined with the much larger number of Midwestern settlers to form a Free-State movement. Many of the New Englanders had embarked for the territory singing songs about making the West “the homestead of the free.”

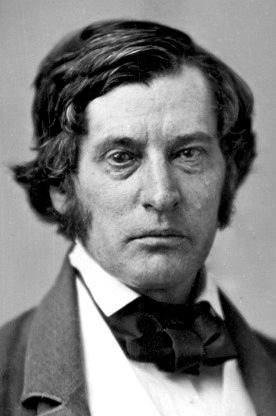

The Midwesterners, however, were represented by former Indiana Congressman James H. Lane, who arrived in the territory, saying that he “would as soon buy a negro as a mule.” Despite their differing beliefs about race and slavery, all of the Northern settlers were united in their outrage at being denied a fair vote at the polls, which was promised them by popular sovereignty. In September 1855, they assembled at Topeka and wrote a constitution for a free state of Kansas. They elected New Englander Charles Robinson as governor and petitioned Congress for admission.

Although many Northerners backed this Topeka movement, it was extra-legal and lacked legitimacy with the federal government. For the next several years, the Free-Staters carried out a precarious balancing act. They refused to obey the territorial or “bogus” legislature and proceeded to arm, often with state-of-the-art Sharps rifles.

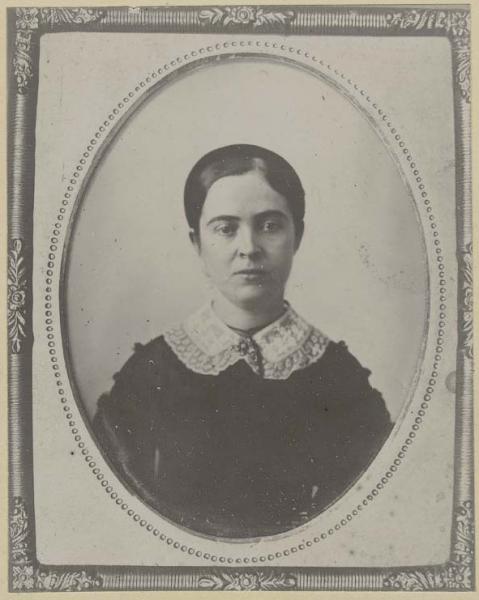

The Free-Staters engaged in a propaganda war. Charles Robinson’s wife, Sara, became even more famous than her husband for her book, Kansas: Its Interior and Exterior Life, which portrayed Free-State sufferings under proslavery, or "Border Ruffian," rule. But fear of retaliation from the federal government, which called the Free-Staters traitors and recognized the proslavery territorial legislature as the legal government of Kansas Territory, restrained Free-Staters from going too far.

Violence Erupts

In opposition to the Free-State movement, proslavery men in the territory formed the “Law and Order Party." Led by territorial officials such as surveyor John Calhoun, a migrant from Illinois, the Law and Order movement seized on lawlessness in the territory to justify acting to suppress the Free-Soil movement in the territory.

Events during the winter of 1855-56 gave the Law and Order movement its chance. In an altercation over a land claim, a Missourian killed a Free-State settler. While the murderer fled back to Missouri, Free-Staters terrorized the neighborhood, warning out settlers and burning houses. Sheriff Samuel Jones arrested the dead man’s friend, but an armed band of Free-Staters liberated his prisoner and took him into the abolitionist New England Emigrant Aid Company settlement of Lawrence. Jones called for help, and territorial governor Wilson Shannon, a tippling Democrat from Ohio, called out the militia. Soon Lawrence was surrounded by proslavery forces in what came to be called the Wakarusa War.

Free-State women, including Lois Brown and Margaret Wood, smuggled arms into the besieged town under their petticoats.

Inside Lawrence, Jim Lane drilled Free-State forces while like-minded women, including Lois Brown and Margaret Wood, smuggled arms into the besieged town under their petticoats. Militia officer George Clarke shot and killed northern settler Thomas Barber when Barber, returning to his farm outside Lawrence, refused to go into the militia’s custody. Barber’s death helped spur a settlement of the dispute. Shannon was anxious to disperse the militia, which seemed increasingly uncontrollable, and a nasty cold spell helped persuade the encamped proslavery men to disband.

But the Free-Staters had neither acknowledged the territorial legislature’s authority nor surrendered the sheriff’s prisoner. In the spring, Sheriff Jones returned to Lawrence, this time to arrest the men who had liberated his prisoner. Free-Staters did not cooperate and Jones was unable to make arrests. Someone shot into Jones’s tent outside town, further inflaming tensions.

When Jones, who had not been seriously injured, released his posse, these proslavery men ransacked Lawrence, destroying the Free State Hotel and throwing the newspaper press, The Herald of Freedom, into the Kansas River. The only casualty was a Missourian, killed by falling masonry from the hotel, but Republican newspapers hailed this as the “Sack of Lawrence.”

Shortly after the Pottawatomie Massacre, Eastern abolitionists seeking to distance Brown from it denied his presence there. However, an 1879 testimony by James Townsley, an abolitionist friend of Brown, indicates that Brown personally led the massacre.

John Brown, a Free-State settler, was on his way to Lawrence with a party of other settlers from southeastern Kansas when they heard that they were too late to protect the town. That night, May 24, Brown led a small party, including his four sons, his son-in-law, and two other men that murdered five proslavery settlers along Pottawatomie Creek.

None of the victims owned slaves, of which there were only a couple hundred in Kansas Territory, but all had connections to the proslavery movement. One, Allen Wilkinson, was a member of the territorial legislature. Another victim named James Doyle, murdered with his two oldest sons, was an officer of the territorial court, and victim William Sherman’s brother ran a store patronized by settlers from Georgia.

A Nation Watches Kansas

Also in May 1856, South Carolina Congressman Preston Brooks administered a bloody beating to Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner in retaliation for insulting remarks Sumner made about Brooks’s uncle, Senator Andrew P. Butler, in a lengthy tirade called “The Crime against Kansas.” Sumner’s speech had violated the Senate’s decorum with its vulgar characterizations of Butler and other proslavery politicians, but the violent attack earned Sumner sympathy and provided further propaganda points as Republican newspapers howled about “Bleeding Sumner.”

Considering the beating of Sumner a violation of free speech, the Massachusetts legislature reelected Sumner, even though he took over two years to recuperate from the attack. Brooks resigned his seat but was reelected. Southerners rewarded him with canes to replace the one he broke over Sumner’s head.

The Sack of Lawrence, the Pottawatomie Massacre, and the attack on Sumner tipped off more violence in Kansas Territory. Charles Robinson was arrested as he traveled to the east and was held through the summer of 1856 as a prisoner with other Free-State leaders at the proslavery territorial capital of Lecompton. The next year, Robinson was tried and acquitted on charges of usurping office. Jim Lane was already in the east and returned in the early fall, helping blaze a new immigrant path, called Lane’s Trail, through Iowa as harassment of Free-State migrants traveling the Missouri River made that route increasingly difficult.

The overwhelmed territorial governor, Wilson Shannon, abandoned Kansas, leaving the territorial secretary and proslavery sympathizer Daniel Woodson in charge. Woodson used the military to suppress the meeting of the Free-State government in Topeka on July 4, 1856.

John Brown took to the brush, leading a guerrilla band that fought skirmishes at Black Jack and Osawatomie, considered by some historians to be the first battles of the Civil War. The proslavery party had their military chieftains, including Henry Clay Pate, captured by Brown at Black Jack, and Henry Titus. When Lane returned to the territory, he immediately entered into the conflict, attacking a proslavery force, the Kickapoo Rangers, at Hickory Point.

By September, the administration of Franklin Pierce had appointed a new territorial governor, John Geary. Democrats expected Geary, a hardened veteran of the war with Mexico and the mayor of San Francisco during the Gold Rush, to restore order to the territory before the presidential elections. Geary ordered any armed bands, Free-State or proslavery, to disband. Jim Lane backed away from the attack on Hickory Point when he learned of the governor’s order. Those of his men who did not disband were arrested.

Henry Titus left the territory to filibuster in Nicaragua. John Brown left it temporarily to raise support for what would become the Harpers Ferry raid. As the violence and disorder declined, Republicans who had trumpeted the summer’s territorial civil war as “Bleeding Kansas” had a less salient issue. The Democrats’ weakness was still evident in that the 1856 presidential nomination did not go to Stephen A. Douglas, the architect of popular sovereignty, but to James Buchanan, an experienced diplomat whose great virtue in the election was his absence from the country during the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act.

Buchanan made it a priority to see Kansas become a state. Geary, increasingly unpopular with proslavery men for his impartiality, left the territory and was replaced by Buchanan’s hand-picked successor, Robert Walker of Mississippi. Meanwhile, the territorial government had started the process of holding a constitutional convention. Arguing that the delegate election process was stacked against them, Free-Staters refused to participate.

The Lecompton and Wyandotte Constitutions

The convention that met at Lecompton in the summer of 1857 was of proslavery men. Walker, believing he had the president’s backing, insisted that any constitution would be submitted to the voters for ratification. While the convention met, the election of a new territorial legislature was held. The Free-Staters now participated and, after territorial officials threw out blatantly fraudulent returns, took control of the territorial legislature.

The Lecompton delegates faced a dilemma. They did not want to embarrass the president, but they did not want a slave-free Kansas either. They devised a ratification formula that did not allow voters to reject the Lecompton Constitution in its entirety. Rather, voters could choose between Lecompton “with” or “without” slavery. “With” slavery meant that Kansas would be a slave state. But “without slavery” it did not abolish slavery, as it merely prohibited future importations of slaves into the territory. Slaves already held in the territory would remain slaves, the rights of property being paramount.

Free-Staters rejected the ratification formula indignantly. They boycotted the election, and Lecompton “with” slavery overwhelmingly passed and was submitted to Congress. Many Northerners, however, agreed with the Free-State objections. Even Senator Douglas decided that Lecompton did not constitute popular sovereignty and called on President Buchanan not to insist on congressional passage.

Buchanan took seriously Southern threats to secede from the Union if Kansas was not admitted as a slave state under Lecompton. He tried to force Northern congressmen—using patronage, threats, and even bribes—to pass the bill. Congressmen Alexander Stephens of Georgia and William English of Indiana staved off an embarrassing defeat by crafting a compromise to appeal to Northern Democrats.

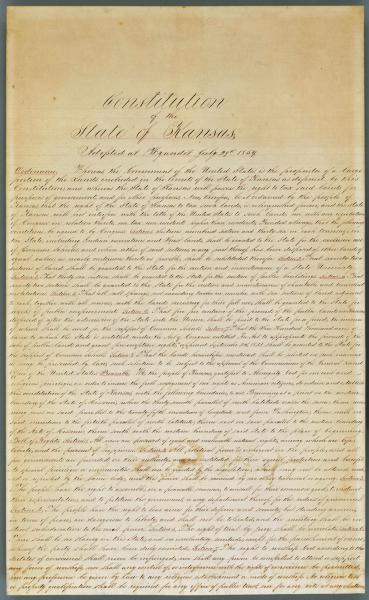

Alleging that there was a problem with the land allotment, Stephens and English crafted legislation whereby Congress returned the Lecompton Constitution to Kansas for another vote. Finally, in August 1858, in an election in which Free-Staters participated, Kansans “killed” Lecompton. Kansas would remain a territory until 1861, when Southern states seceded from the Union and Kansas was admitted under the Free-State Wyandotte Constitution.

Toward Harpers Ferry and War

Kansas nonetheless remained an intense national controversy, especially in the 1858 senate election in Illinois. Stephen Douglas, running for re-election, faced a powerful challenge from Republican Abraham Lincoln. In lengthy debates throughout the state, the two men argued over the meaning of popular sovereignty and its effects on Kansas and the nation.

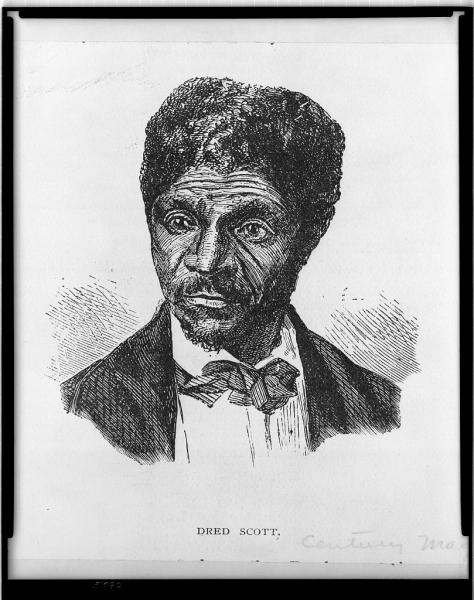

Despite the recent Dred Scott decision, in which the Supreme Court ruled that the Missouri Compromise’s prohibition against slavery was unconstitutional, Douglas insisted that settlers could keep slavery out of a territory by refusing to enact a slave code. Lincoln accused Douglas of being part of a conspiracy to nationalize slavery, of which the Kansas-Nebraska Act and Dred Scott were both pieces.

The most profound difference between Lincoln and Douglas was that Douglas took a “don’t care” policy by insisting that white men’s rights to vote on slavery were the highest morality. Lincoln insisted that slavery was a moral wrong, with a stigma placed on the institution by the nation's founders, and should not be expanded. Although the Republicans, led by Lincoln, made a strong showing, the apportionment of the state legislature was such that Douglas was reappointed to his Senate seat (prior to the 17th Amendment in 1913, U.S. senators were not directly elected) and kept his political career alive.

Americans paid less attention to Kansas after the Lecompton controversy subsided, but all was not quiet in the territory. In May 1858, a proslavery band gathered up a group of Free-State men and shot them down along the Marais des Cygnes River. Free-State guerrilla James Montgomery continued activities in southern Kansas, raiding Fort Scott and killing a local man.

John Brown returned to Kansas in the winter of 1858-59 and led a raid to liberate a group of Missouri slaves. Brown’s return to the territory proved temporary. With the support of Eastern backers known as the Secret Six, Brown used his credentials as “Captain” Brown, of Kansas fame, to raise money for the attack on Harpers Ferry. Despite the failure of the raid, Brown’s subsequent martyrdom fixed him in the public mind as the archetypal figure of Bleeding Kansas.

Brown was not a typical Free-Stater. He had arrived in the territory after the Free-State movement formed, participated only peripherally in Free-State politics, and disdained more reserved Free-State leaders, including Robinson and Lane, as “old women.” But like abolitionist Lydia Maria Child, many Americans viewed Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry as evidence of how Bleeding Kansas had polarized the national debate over slavery.

When he went to the gallows, Brown was not alone in believing that “the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with Blood.” Blood had been shed in Kansas, and still more blood would be shed in the years to come.

Suggested Reading:

Etcheson, Nicole. Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004.

Horwitz, Tony. Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid That Sparked the Civil War. New York: Holt, 2011.

Oertel, Kristen Tegtmeier. Bleeding Borders: Race, Gender, and Violence in Pre–Civil War Kansas. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2009.

Cite This Page:

Etcheson, Nicole. "Bleeding Kansas: From the Kansas-Nebraska Act to Harpers Ferry" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Wednesday, April 17, 2024 - 12:09 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/essay/bleeding-kansas-kansas-nebr...

Rights/Licensing:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License