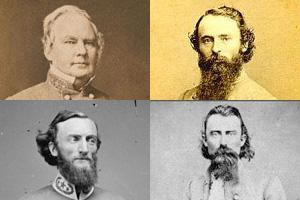

Sterling Price with his three leading generals, James F. Fagan, John S. Marmaduke, and Joseph “Jo” Shelby. Images courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution; the Library of Congress; Wikimedia Commons.

By Jason Roe, Kansas City Public Library

Each month in 2014, the Library will commemorate the sesquicentennial of the Civil War in Missouri and Kansas with a post derived from the thousands of primary sources that are digitized and incorporated into this website. The Library and its project partners collaborated to assemble this rich repository from the collections of 25 area archives, combining it with interpretive tools and original scholarship produced by nationally recognized historians.

The “Army of Missouri” Invades Missouri

September 1864 marked a pivotal moment in both the East and West. In the East, the month began with outstanding news for Unionists, as the city of Atlanta surrendered to Major General William T. Sherman on September 2. In stark contrast to the previous few months, during which the Union Army sustained some 55,000 casualties in General Ulysses S. Grant’s “Overland Campaign” alone, Northern political observers believed that the capture of Atlanta all but assured President Lincoln’s reelection in November. Prior to Atlanta’s surrender, the drawn-out and brutal nature of the war seemed to have weakened Northern morale to such an extent that Lincoln would lose the upcoming election, which would likely lead to a negotiated peace settlement with the South. Lincoln himself agreed with this assessment in the summer of 1864, until the capture of Atlanta promised to bolster Unionists’ resolve to continue the war.

In the West, however, the news from Atlanta did not deter Confederate Major General Sterling Price, who continued to believe that a stunning Southern victory could sway Northern sentiments back against the Lincoln administration. In August, Price received orders to raise an army that would invade the state of Missouri, capture the strategic city of St. Louis, raise thousands of badly needed recruits for the Confederacy, and potentially secure the state as a member of the Confederacy. Price and others hoped that the invasion would offset the surrender of Atlanta and cast doubt on the possibility of a Northern victory. Lincoln and the Northern cause in the war, Price believed, could still be defeated through military setbacks.

On September 15, Price’s “Army of Missouri” converged at Powhatan, Arkansas, and advanced to Pocahontas the following day. They divided into three divisions, or “columns,” which would allow them to advance to the northeast while foraging and recruiting along three parallel routes. On September 19, the three columns entered Missouri and split off. Price’s subordinate generals, James F. Fagan, John S. Marmaduke, and Joseph “Jo” Shelby, could each boast of significant accomplishments in their own right. With their talent and some 12,000 cavalrymen and 14 cannon, concentrated in one army, they hoped that the isolated and outnumbered Union defenders would melt away or be crushed in the wake of the Confederate advance.

The routes taken by the three columns of Price’s

Missouri Expedition.

(View Price's Raid in a larger map.)

Price’s estimate that as many as 30,000 potential recruits awaited him in his home state was unrealistic, but his supporters still had reasons for optimism. On the opposing Union side, historian Mark A. Lause estimates that perhaps only 11,000 federal soldiers were deployed across the state of Missouri at the beginning of September, primarily due to tens of thousands of men being transferred to the East to support the campaigns of Grant and Sherman. Contributing to the apparent federal weakness in the state, pro-Southern “bushwhackers” elevated their guerrilla warfare against civilian and military targets as word spread that Price was entering the state. With a concentrated force of fast-moving cavalry, the “Missouri Expedition” seemed to have an opportunity to move quickly on St. Louis before Union reinforcements could arrive.

Despite the apparent advantages held by Price, the outcome was still in doubt as his cavalry crossed into Missouri on September 19. His men were on the offensive in a war that favored defensive positions. According to Price’s own reports, 4,000 of his 12,000 cavalrymen were unarmed, most likely meaning that they carried personally supplied small arms and could not be resupplied with ammunition as easily as the 8,000 men who were issued standard weapons. According to historian Donald L. Gilmore, an officer named Major Shaler further testified after the raid that discipline was almost nonexistent, owing to the army being hastily assembled from “conscripts, absentees without leave from their commands and deserters, and but a few volunteers.” Gilmore goes on to describe the Army of Missouri as having been little better than a large "mob" on horseback. The problems of discipline would only be compounded if Price succeeded in his plans of recruiting thousands of bushwhackers and conscripting untrained civilians. Still, the advancing force presented a significant challenge to Union control of the state.

Massacre at Centralia

Many of the potential recruits for Price’s Army of Missouri would have to come from among Missouri’s guerrilla warriors, who Unionists derisively referred to as “bushwhackers.” Acting on cue, the bushwhacker’s guerrilla activity spiked before and during Price’s invasion. Unfortunately for the Southern cause, the bushwhackers did little to disprove their reputation as eager participants in the savagery and plunder that had long reigned on both sides of the conflict. By the summer of 1864, even many Southern-leaning Missourians had had enough of the irregular warfare that was being waged against the Union military and civilian targets.

The violence ranged across the state. Lucie Davis, a resident of Clay County, Missouri, wrote in a letter that, “The bushwhackers are about to take this country. They robbed the mail yesterday between Missouri City and Liberty.” Alex M. Bedford, a Confederate soldier from Savannah, Missouri (located north of St. Joseph), learned of the recent guerrilla violence in letters from his wife. He was being held in a federal prisoner of war camp at Fort Delaware, Delaware, and despite clearly siding with the Confederacy for the duration of the war, he wrote the following to his wife on August 2: “I am done on bushwhackers[.] let them call their name what they will[,] it is a dishonorable warfare.”

On September 27, an incident at Centralia, in the central part of the state, quickly became the most notorious event instigated by bushwhackers in 1864. The Union Army had been responding to bushwhacker attacks—most notably the massacre of between 160 and 190 men and teenaged boys at Lawrence, Kansas, in August 1863—by evicting the civilian populations of counties that harbored bushwhackers and, more directly, by routinely executing suspected bushwhackers without trial. In response, some bushwhackers escalated the brutality of their reprisals, with the most notable instances instigated by William T. Anderson, who had already earned his nickname, “Bloody Bill.” A former “captain” of Quantrill’s Raiders and veteran of the raid on Lawrence, Anderson counted plenty of grievances to justify his actions. In the previous year, for example, his sisters had been arrested as suspected Confederate spies, and one of them died in the collapse of a makeshift prison in Kansas City.

For more details about the massacre and battle at Centralia, read our encyclopedia entry on the Centralia Massacre.

With numerous reprisals on both sides, Anderson’s rage continued to build in 1864, and his men gained a reputation for scalping and otherwise defiling the bodies of the Union soldiers they killed. By September, reports indicate that Union soldiers were, in turn, scalping any of Anderson’s men who were killed. The violence surrounding Anderson’s band of guerrillas culminated at Centralia on September 27. Roughly 80 of Anderson’s men stopped a train at Centralia, removed 23 Union soldiers who were on leave following their participation in the Battle of Atlanta, and shot 22 of them. Later on the same day as the “Centralia Massacre,” as it came to be known, Anderson’s men fought a battle against a pursuing Union force outside of town and wiped out all but 32 of the 155 inexperienced federals.

For Sterling Price, who styled himself as a nobler breed of general, the prospect of recruiting thousands of bushwhackers, many of whom were known for scalping and sacking towns for personal gain or revenge, was unpalatable at best. But Price’s entire plan for the Missouri Expedition hinged on expanding his forces as he advanced, and it would only be in October that he would start to rendezvous with large numbers of guerrillas.

Fighting at Pilot Knob

On precisely the same day that “Bloody Bill” Anderson’s men massacred and battled Union soldiers at Centralia, Price waged his own battle that would place the success of his cavalry raid into doubt in the space of just one day. As the Army of Missouri moved in the direction of St. Louis, he learned that Union reinforcements were already arriving there. Generals Shelby and Marmaduke urged Price to move as quickly as possible to take the city before it was too late. Instead, Price, with the support of Fagan, elected to attack Fort Davidson, outside of Pilot Knob, Missouri, about 90 miles to the southwest of St. Louis.

The main argument against Price’s decision centered on the fact that Fort Davidson was garrisoned by a relatively small force made up mostly of infantry. Price’s cavalry, still mostly unburdened by plunder, could simply outmaneuver the infantry defending the fort and move quickly on St. Louis. Price, on the other hand, reasoned that he could take Fort Davidson quickly and with few losses; capture arms, powder, and other supplies; intimidate the Union defenders of Missouri; and boost the morale of his men before moving on St. Louis, assuming that he still thought St. Louis could be taken at all. In any case, it appeared to be a confident move from a superior force and a general who sat astride a horse he called Bucephalus, named after the horse ridden by Alexander the Great.

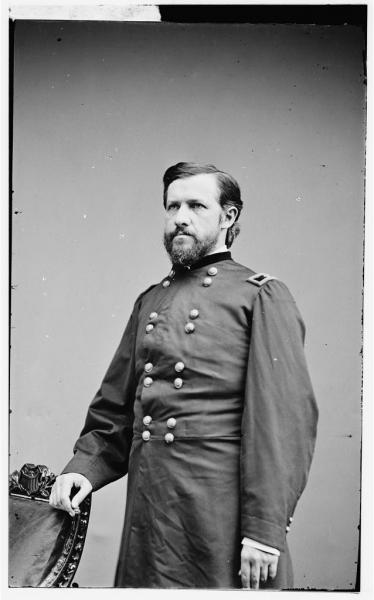

Fort Davidson’s commander also presented a tempting target in his own right. The fort was defended by 1,450 men under the command of Brigadier General Thomas Ewing Jr., the former commander of the District of the Border, which had been based in Kansas City. In the previous fall, Ewing’s controversial General Order No. 11 had removed most of the rural civilian populations of four counties, and the political backlash from his order likely contributed to his removal from command as a part of the reorganization of the District of the Border at the beginning of 1864. In March he was reassigned to the District of St. Louis, and he continued to be a primary target of the hatred of Missouri’s bushwhackers. Ewing took command of Fort Davidson on September 26, just one day before Price and the two columns under command of Fagan and Marmaduke converged on his position.

Due to their mutual disagreement, Price replaced Marmaduke with the untested General John B. Clark Jr. for the battle. He then ordered multiple assaults on the fort throughout the day on September 27. Ewing’s artillery was able to push back Price’s artillery, at least temporarily, preventing the immediate destruction of the fortifications. (Later, Price claimed that Ewing used pro-Southern civilians as hostages to dissuade Price from using his artillery to full effect, which would have been a violation of the unofficial laws of war. But that accusation remains unsubstantiated by modern historians). Ewing also rejected Price’s demand to surrender, replying that he did not want his garrison, made up largely of African American soldiers, to be massacred upon surrender as black soldiers had been at Fort Pillow, Tennessee, in April. As night fell, Price had lost roughly 1,000 men to Ewing’s 200, but he still held an overwhelming advantage in numbers and would assuredly take the fort.

Price completely failed to anticipate what would happen after dark. In a bold move, Ewing quietly prepared his men to abandon the fort and sneak out under the cover of darkness. They loaded up as many supplies as they could carry, attached hay to their horses’ hooves, and covered the fort’s drawbridge with blankets and straw to soften the noise. At an hour past midnight on September 28, the Union garrison slipped out of Fort Davidson under cover of darkness. Remarkably, Price had left a hole in his lines large enough for Ewing’s men to escape through, and Price’s men mistook the movement as their own soldiers. A few Union men remained behind to allow Ewing time to escape, and then they lit a slow-burning trail of powder to the fort’s powder magazine as they made their escape on horseback. The magazine detonated at around 4:00 a.m., leaving behind a huge crater and nothing useful for Price’s men.

Price gained nothing of strategic value from the Battle of Fort Davidson. Moreover, including the maneuvers before and during the battle, as well as time spent futilely tracking Ewing’s men afterwards, Price’s invasion was delayed by up to five days, which allowed the Union critical time to reinforce St. Louis and organize an army potentially large enough to repulse the Army of Missouri.

For his actions at Fort Davidson, General Ewing received a personal note of gratitude from President Lincoln. On the other side, Price had to turn his sights away from St. Louis by the last day of September 1864, and on October 1 his army moved westward toward the state capitol at Jefferson City, where he could still hope to install a state government loyal to the Confederacy. The fate of the Missouri Expedition would have to be decided in October.