By Christopher Phillips, University of Cincinnati

Major General Sterling Price’s unsuccessful cavalry raid of September and October 1864, the largest Confederate cavalry raid of the war, sought to capture St. Louis and recover Missouri for the Confederacy. Price believed the expedition would spur recruiting, contribute to Abraham Lincoln’s defeat in the November presidential election, and perhaps end the war.

On September 19, Price’s Army of Missouri, consisting of three divisions under John S. Marmaduke, James F. Fagan, and Joseph Shelby and totaling 12,000 men and 14 cannon, entered Missouri from northern Arkansas. Traveling in three columns with two divisions, Price engaged 1,500 fortified federals under Brig. Gen. Thomas Ewing at Pilot Knob. Price unwisely ordered a frontal assault on the earthen structure and took more than 1,000 casualties. During the night, Ewing blew up the powder magazine and escaped with his command, having suffered fewer than 100 casualties.

Discovering the following morning that Ewing had escaped, Price sent Shelby and Marmaduke in pursuit. But Price decided not to try to capture St. Louis due to the 4,500 federal cavalry advancing under Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton to reinforce Ewing, and an 8,000-man federal infantry corps under Maj. Gen. A. J. Smith, positioned south of St. Louis. Still, Price believed that the presence of his army would entice volunteers and secure supplies. On September 30, Price began marching westward, following the south bank of the Missouri River and destroying railroad bridges and track. Recruits proved sparse and undisciplined. His languid pace allowed nearly 7,000 federal troops to fortify Jefferson City. Harassed by Pleasonton's cavalry, Price bypassed the state capitol and proceeded westward.

At Boonville, Price added some 2,000 recruits, bringing his total force to 15,000. Many were unarmed and untrained. Looters and pillagers abounded, many of them guerrillas who targeted Unionists, especially Germans and African Americans, both civilian and enlisted. Their exploits caused (Confederate) Governor Thomas Caute Reynolds to write to Price, claiming that this ravaging made it difficult to supplant the state’s pro-Union provisional government. Seeking arms, Price’s regulars captured garrisons at Glasgow and Sedalia. Throughout the slow march, federal cavalry skirmished with Price’s rear-guard under Marmaduke, who protected the cumbersome 500-wagon supply train and some 5,000 cattle.

Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans, department commander, mobilized forces to trap Price’s army. Pleasonton’s cavalry dogged Price’s rear to slow his progress, while Smith's infantry hastened from St. Louis to flank the Confederate column and 4,500 Union veterans under Maj. Gen. Joseph A. Mower moved northward from Arkansas. Maj. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis massed more than 15,000 troops near the Kansas border. On October 15, he ordered into Missouri three brigades, mostly militia, under Maj. Gen. James G. Blunt. Most remained near the Big Blue River, six miles east of Kansas City, while 2,000 regulars occupied Lexington. These separate federal forces numbered more than twice Price’s force.

Turning southward, Price hoped to position his force between Blunt and Smith and defeated each in turn before turning on Curtis’s militia. On October 19 and 21, Shelby pushed back Blunt’s lead units at Lexington and the Little Blue River and moved ahead toward the main force at the Big Blue, entrenched on the steep west bank. After a sharp skirmish in which the federals’ superior firepower briefly pushed back the advancing Confederates, Price’s superior numbers soon threatened to turn both of the federal flanks, forcing them to retreat.

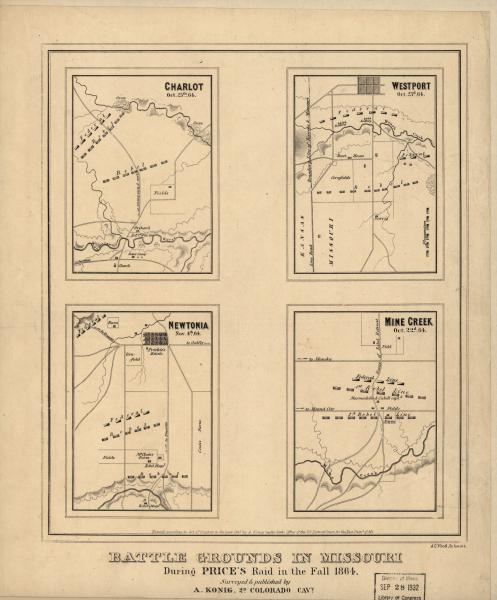

On October 22, after three hard hours of fighting at Byram’s Ford, the main crossing of the Big Blue, Price’s flanking movement upstream pushed across the river and fell upon Curtis’s exposed right. As the federals withdrew, Shelby’s division crossed the Big Blue and drove toward Westport, south of which Curtis reformed his line during the night.

In Price’s rear, Pleasonton crossed the Little Blue, drove Marmaduke’s division through Independence and pushed it nearly to the Big Blue. With his army in danger of being trapped by converging columns and its large wagon train captured as it crossed the steep ford, Price decided to attack the federals near Westport in hopes of moving southward.

At daybreak on October 23, Shelby’s division attacked the federal position. During several hours of fighting, opposing lines of horsemen charged and countercharged in the grassy hills along Brush Creek while Pleasonton assaulted Marmaduke, who defended Byram’s Ford. Both sides took heavy losses. At noon, Marmaduke’s troops, out of ammunition, routed across the prairie with federal horsemen in pursuit. Hundreds of Marmaduke’s men were captured in the retreat. Simultaneously, Curtis and Blunt attacked Shelby’s right flank, nearly breaking the Confederate line, and federals pushed through the last defended ford at Hickman’s Mill.

The Battle of Westport proved to be Price's spectacular downfall, as the largest and the last major action which took place in the trans-Mississippi region.

Pressed on three sides, Price ordered a retreat southward, leaving Shelby to fight a rear guard. As Marmaduke and Fagan streamed toward Little Santa Fe, only Shelby’s dogged defense saved Price’s army from complete destruction. The Battle of Westport proved to be Price's spectacular downfall, as the largest and the last major action which took place in the trans-Mississippi region. Exact casualties are unavailable, but estimates are nearly 1,500 dead and wounded on each side.

View Price's Raid in a larger map

As Price fled southward along the Military Road, the ponderous wagon train allowed federal pursuers to overtake the fleeing Confederates in Kansas, at Trading Post, Mine Creek, and Marmiton River, 60 miles south. After the three encounters, during which Marmaduke was captured (at Mine Creek), Price burned nearly a third of his wagons. Skirmishing continued, and Blunt caught up with Price’s retreating column at Newtonia, Missouri, on October 28. Shelby again managed to drive off the advancing federals. The next day, Rosecrans recalled all troops in his Department of Missouri, leaving Curtis with just 3,500 cavalry continuing the chase. Price soon dispersed his forces and marched through Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) to Texas.

When the column returned to Laynesport, Arkansas, on December 2, Price’s army had traveled 1,488 miles. Missouri remained under Union control, Lincoln was reelected, and the Confederate cause on the Western border had been dealt a serious blow. The Missouri Expedition had failed to achieve any of its objectives at a loss of an estimated 4,000 men, mostly to desertion.

Suggested Reading:

Castel, Albert E. General Sterling Price and the Civil War in the West. Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1968.

Lause, Mark A. Price's Lost Campaign: The 1864 Invasion of Missouri. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2011.

Shalhope, Robert E. Sterling Price, Portrait of a Southerner. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1971.

Cite This Page:

Phillips, Christopher. "Price’s Missouri Expedition (or Price’s Raid)" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Friday, April 19, 2024 - 12:12 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/encyclopedia/price-missouri-exped...