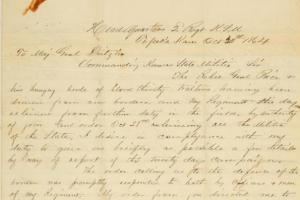

Firsthand account of the Battle of the Blue, by Colonel G.W. Veale, 2nd Regiment, Kansas State Militia.

By Jason Roe, Kansas City Public Library

Each month in 2014, the Library will commemorate the sesquicentennial of the Civil War in Missouri and Kansas with a post derived from the thousands of primary sources that are digitized and incorporated into this website. The Library and its project partners collaborated to assemble this rich repository from the collections of 25 area archives, combining it with interpretive tools and original scholarship produced by nationally recognized historians.

Price's "Missouri Expedition" Turns West

Rebs march on Kansas City[.] start this way on tomorrow morning—goodbye—If I don't return remember I fought for the right. [General William Rosecrans] says—he is afraid he will not be able to check the Rebs—farewell perhaps forever.

On October 12, 1864, these were the last words written by a soldier named Samuel Worthington to his father before he departed from Fort Riley to oppose the advancing Confederate "Army of Missouri," commanded by Major General Sterling Price.

Price's incursion into Missouri began the previous month, on September 15. With a fast-moving cavalry force of up to 12,000 men, he hoped to gain desperately needed recruits for the Confederacy, capture the strategic city of St. Louis, and possibly claim the state of Missouri for the Confederacy, thus casting a shadow on President Lincoln's re-election bid in November. Although the surrender of Atlanta, Georgia, on September 2 had seemingly secured Lincoln's re-election and Northern support for continuing the war, Price and his followers hoped that a devastating blow in the West might still result in Lincoln's defeat and the eventual recognition of the Confederate States of America.

Due to the rapid deployment of Missouri recruits to the East in support of the offensives being led by General Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman, the Union presence in Missouri had dwindled to as few as 11,000 soldiers, scattered across the state. Price's strategy relied on the use of overwhelming force and rapid movement to throw the Union defenders off balance before reinforcements could arrive. For sheer psychological effect, Price's Raid was already succeeding at the beginning of October, as Samuel Worthington summarized in his letter to his father: "I don't see how we can withstand the onward progress of Gen[.] Price, as there are not in the Dept[.] of Missouri & Dept[.] of Kansas troops sufficient to whip him, unless reinforcements arrive from the East." Price, however, soon blundered by spending up to five days and losing 1,000 men in assaults on a small Union garrison at Fort Davidson, near Pilot Knob in the southeastern part of the state. Although Price's "Army of Missouri" captured the fort, it failed to acquire arms or ammunition, and the delay allowed Union reinforcements time to bolster their positions at St. Louis and the state capitol at Jefferson City.

As October began, Price's men were positioned between 35 and 50 miles west of St. Louis, the closest they would ever get to their primary target. As the cavalry raiders maneuvered around the city and skirmished with its Union defenders, they destroyed rail depots and tracks, recruited men, and continued to plunder various towns. The raiders turned west toward Jefferson City but found the federal resistance too strong, leading them to head toward the next targets on their list: Kansas City and possibly Fort Leavenworth. Along the way, they were joined by hundreds of recruits, although many were poorly trained, unarmed, or otherwise ill-equipped.

Read an encyclopedia entry about Price's Missouri Expedition, by professor Christopher Phillips, University of Cincinnati.By October 10, the Army of Missouri arrived at Boonville, 100 miles to the east of Kansas City, where the situation would only get worse. Boonville was situated inside the "Little Dixie" part of the state and was home to many of Price's men. A large portion of them went on unauthorized leaves to visit their families. Others plundered Boonville despite its pro-Southern proclivities, which only added to the slow, 500-wagon supply train filled with provisions as well as loot from the raid. While Price's army delayed at Boonville, General Alfred Pleasonton led a pursuing Union cavalry force consisting of 4,500 men, closing in on Price's position from the east. Meanwhile, in Kansas, Governor Thomas Carney raised a force of state militia to check Price's advance to the west. Major General Samuel R. Curtis commanded some 15,000 regular soldiers and militia from the Department of Kansas along the border, and the Union forces converging on Kansas City totaled nearly 30,000.

From the outset of the raid, Price intended to rely on support from hundreds or thousands of Missouri's "bushwhackers," the controversial but effective guerilla forces who attacked military targets and Unionist civilians across Missouri and eastern Kansas. Price rendezvoused with two of the most notorious of these bushwhackers at Boonville: William Clarke Quantrill, famed for his raid on Lawrence, Kansas, and William "Bloody Bill" Anderson, one of Quantrill's former "captains" known for his reckless leadership and unchecked brutality. The disparity between Price's regular enlistees and the bushwhackers became glaringly obvious as Anderson's men appeared on horseback with the scalps of Union soldiers they had killed in the Centralia Massacre and an ensuing battle some two weeks before. Price demanded that they abandon the scalps before ordering Anderson and his men to destroy bridges on the North Missouri Railroad. Anderson was unsuccessful. Meanwhile, Quantrill received orders to destroy bridges on the Hannibal & St. Joseph line but—due to a lack of followers, personal disdain for Price, or a belief that the Confederate cause was already lost—Quantrill did not carry out his task.

As Price's Army of Missouri resumed its westward advance, Pleasonton's cavalry nipped at its heels. On October 19, Price won handily at Lexington against a force of 2,000 commanded by Major General James G. Blunt, but Blunt's strategy of skirmishing and slowing Price was working. On October 21, Price overran Blunt's forces again at the Little Blue River, about 14 miles east of Kansas City. At the Little Blue, B.F. Dawson, a soldier in Company B of the 2nd Kansas Militia, described being outflanked by one of Price's divisions, the "Iron Brigade," under command of General Joseph O. Shelby. According to Dawson, Company B was "charging across that lane into that locust grove and drove the [rebels] out from behind the fences." After a countercharge by the Confederates, Company B was overwhelmed and Dawson was taken prisoner along with about 30 others. Colonel G.W. Veale, also from the 2nd Kansas Militia regiment, described the battle less charitably in an official report:

As it was I was sacrificed, being ordered to fight six times my number of Prices veterans & Bush Whackers with my raw militia, and who is to blame? I ask who scattered the troops all over the country without concert of action. tis not for me to say. I can only say that I obeyed orders and by so doing I lost twenty four brave Kansans killed[,] about the same number wounded[,] and sixty eight taken prisoners.

Battle of Westport

What seemed to be a disgraceful route for front-line Union soldiers at the Little Blue was part of a larger stratagem for Major General Curtis, who intended to slow Price's advance and ultimately surround the Army of Missouri on three sides. Curtis attempted to stop Price's advance at the Big Blue River about five miles southeast of Kansas City, but he was outflanked at Byram's Ford, where Price crossed the Big Blue on October 22. Curtis ordered General Blunt to establish a defensive line south of Brush Creek near the town of Westport, Missouri, several miles south of Kansas City. Kansas militia, including a brigade under command of an infamous "jayhawker," Charles "Doc" Jennison, closed in from the west as Pleasonton's cavalry continued to pressure Price's supply chain from the east. Partially surrounded and outnumbered 2-1, Price nonetheless decided to fight the next day by first attacking the bulk of the Union army under Curtis, and hopefully engaging the surviving Union forces separately.

Learn more about the Battle of Westport in an encyclopedia entry by Dr. Terry Beckenbaugh, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College.On the evening of October 22, the Union forces in range of Price's men prepared for battle and were unsure of the outcome. One Union soldier, James Griffing, heard of reports that Price had arrived at Westport with 20,000 to 40,000 men. Such a number was unfeasible for a Confederate army on the Missouri-Kansas border, so far away from supply lines, but those logistical limitations are more obvious to modern observers than they were to soldiers at the breastworks on the eve of a battle. Griffing fretted in a letter to his wife on the morning of October 23 that, "as he [Price] is pretty well surrounded, I am looking for a pretty severe contest to day. Our company may be in the midst of a most terrible slaughter."

That morning, two divisions of the Army of Missouri, commanded by major generals Joseph O. Shelby and James Fagan, attacked Blunt's men. The Confederates were the main aggressors and held an early advantage, but their inadequate supply of ammunition halted many of their advances as they had to continually reload and re-secure their supply lines. Blunt's men were driven north across Brush Creek to join Curtis's main force, but as the fighting dragged on, the Kansas militia had time to close in on Price's left flank and join the fight.

Read a firsthand account of the Battle of Westport by James H. Lane.At 11 a.m., Curtis made preparations to cross a shallow point of Swan Creek and made a flanking maneuver around Price's army. Sealing the Confederate's fate at nearly the same time, Pleasonton's cavalry secured Byram's Ford and captured an adjacent hill that had been the defensive position of Price's 3rd Division and the Army of Missouri supply wagons, under command of General John S. Marmaduke. By the early afternoon, the beleaguered Army of Missouri faced the prospect of a route and barely managed to escape to the south without being crushed.

During all of the fighting, James Griffing observed the smoke from a distance of five miles to the north. Around 2 p.m., Griffing's company was ordered to secure defensive breastworks that were set up by "Doc" Jennison. Of the battle, Griffing wrote to his wife:

They are at present fighting a tremendous battle about five miles south of this, the wounded are being brought in, in large numbers. We can see the smoke of the battle very plainly, but the wind is quite unfavorable and the continued talking and cheering as the dispatches come in prevents our hearing much of the thunder of the artillery. Still later our men have cut off his long train of commissaries and taken a large amount of his pillage and Price is going South just as fast as he can. An order has come requiring just as many of our men as possible to get horses and pursue after him.

In sum, each side lost some 1,500 killed, wounded, or missing in the Battle of Westport, but Price's cavalry and the remainder of its supply wagons were consigned to a hasty retreat while being pursued by Union cavalry.

Debacles at Mine Creek and Newtonia

Although Westport proved to be decisive (and has since been called the "Gettysburg of the West" as the largest battle fought west of the Mississippi River), such an outcome was not immediately apparent after the battle ended. Price managed to escape to the south with the bulk of his army intact, and the pursuing federal cavalry numbered half of Price's forces. It would take more battles, particularly at Mine Creek, Kansas, and Newtonia, Missouri, to determine whether the Missouri Expedition would end with a tactical retreat or with a crushing, permanent defeat.

October 25 marked a day even worse than the Battle of Westport for the Army of Missouri. It started with an attack by Alfred Pleasonton's pursuing cavalry force at a crossing on the Marais des Cygnes River. More significantly, at just before noon the same day, two Union brigades totaling 2,600 men and commanded by Colonel Frederick Benteen and Colonel John F. Phillips, caught up with two of Price's divisions, commanded by John S. Marmaduke and James Fagan, just as the 7,000 or so Confederates crossed the muddy banks of the creek. Phillips and Benteen aggressively charged on horseback despite being outnumbered more than 2-1. The Confederates, who were still mounted, desperately trying to cross the creek and mostly carrying single-shot muskets, panicked and were routed. Marmaduke was captured, and over 1,200 others were killed, captured, or wounded.

Accounts from Unionists shortly after the Battle of Westport expressed dismay that the Union forces under General Curtis were not able to crush Price's Army of Missouri. Learn more.Making matters worse at Mine Creek, the Army of Missouri had been so ill-equipped for its raid that many of the cavalrymen relied on clothing captured from Union soldiers during their epic journey across Missouri. Beginning in 1862, the Union Army considered enemies captured in Union uniforms to be spies or bushwhackers who did not fight according to the laws and customs of war and routinely executed them on sight. As many as 300 regular Confederate soldiers from the Army of Missouri wore the Union blue coats and met this fate at Mine Creek, although some of them were actual bushwhackers.

Samuel Worthington, the soldier from Fort Riley who previously explained to his father that he would be sent to oppose Price's army, described the Battle of Mine Creek in another letter to his father, saying he was involved in "five grand Cavalry charges during the day." His description of the main charge at Mine Creek was poignant, if brief:

I was in the left wing of the Charging force and we all came near being taken in—My horse was so hard mouthed I could do nothing with him. I had [emptied] both my revolvers before I got to the Rebel line of Battle and he with three other horses charged clear through the lines[.] Strange to say, none of us was scratched in the least, although we were in a perfect shower of balls.

In Worthington's assessment, "The Rebs are whipped completely." It was the largest and most significant battle in the state of Kansas.

A third, smaller battle occurred later in the same day at another river crossing, this time on the banks of the Marmaton River in Kansas. The final blow to the retreating Army of Missouri came on October 28 at Newtonia, in the southwest part of the state. General Blunt's cavalry attacked a mounted infantry division under command of General Shelby, causing 250 Confederate casualties. Although it was a relatively small engagement, Newtonia was the last battle of Price's Missouri Expedition, and the Army of Missouri broke apart immediately afterward. The army's scattered remnants retreated through Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), and either dispersed or followed Price to Texas. There, Price stubbornly attempted to retain his command and would eventually return to Arkansas in December with 3,500 men.

Besides ending the threat of a formal Confederate offensive in Missouri, a number of bushwhackers were killed, captured, or accompanied Price on his retreat into Confederate territory. Missouri's bushwhackers suffered a final setback on October 27, when a small Union force ambushed "Bloody Bill" Anderson's guerrillas and Anderson received a shot to the head that killed him instantly. Two photographs were taken of Anderson's body at the Richmond, Missouri, courthouse, and Union soldiers cut off his head and placed it on display on a telegraph pole. The defilement of his body was but one of countless reprisals along the Missouri-Kansas border, both before and during the Civil War. After these events, guerrilla activity was severely curtailed and a measure of stability promised to return to the Missouri-Kansas border for the first time since the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854.

At the beginning of October 1864, Union military control of Missouri had (at least nominally) been in jeopardy, and Sterling Price believed he still had a chance to tilt the national elections against Abraham Lincoln and bolster the Confederate cause. By the end of the month, Price's Army of Missouri was crushed, bushwhackers presented little threat to the Union position in Missouri, Lincoln was all but assured of re-election to a second term, and the Union appeared to be well on its way to winning the war in the East and West.