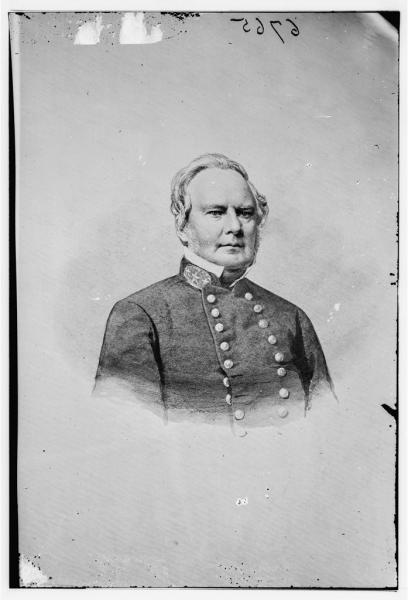

Brig. Gen. John S. Marmaduke led the forces that captured Capt. Richard M. Hulse at the Battle of Chalk Bluff. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

By Jason Roe, Kansas City Public Library

Each month in 2014, the Library will commemorate the sesquicentennial of the Civil War in Missouri and Kansas with a post derived from the thousands of primary sources that are digitized and incorporated into this website. The Library and its project partners collaborated to assemble this rich repository from the collections of 25 area archives, combining it with interpretive tools and original scholarship produced by nationally recognized historians.

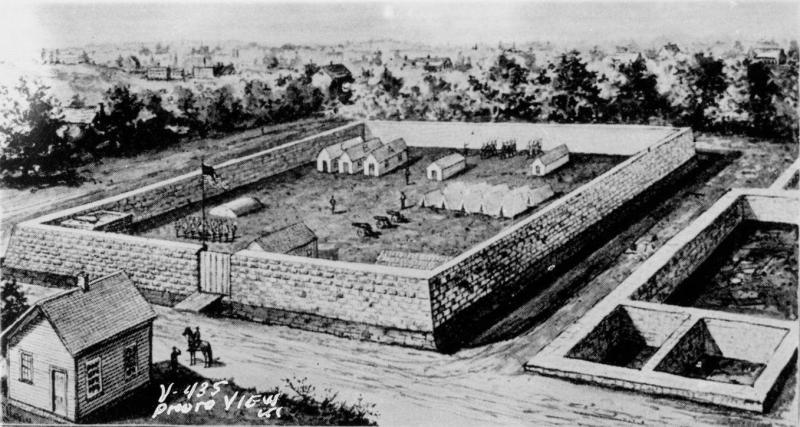

Fortifying a Missouri Town

“I would rather work my men six months on fortifications to protect them from the Enemy than to be taken again prisoner,” Captain Richard M. Hulse wrote to his parents on May 7, 1864. Hulse referred to the efforts of 58 cavalrymen under his command in Company H, 2nd Regiment of the Missouri State Militia. Stationed in Dallas, Missouri, in the southeast part of the state, they worked to block off windows and barricade the doors of the Court House and secure their horses inside a fortification connected to that building.

Drawing on his personal experience, Hulse had good reasons for setting up defenses at the Company H headquarters. As a whole, the state of Missouri suffered from recurrent battles and guerrilla warfare between the opposing sides, and the town of Dallas, which would be renamed Marble Hill in 1868, had already endured significant destruction from a small raid of 120 Confederates in 1862.

Hulse’s motivations, as revealed in the letter, especially stemmed from his capture and imprisonment at the Battle of Chalk Bluff on May 1-2, 1863. That battle took place in Clay County, Arkansas, and Dunklin County, Missouri, and resulted in a tactical victory for the Confederacy but a strategic victory for the Union due to significant casualties sustained by the invading Confederate forces. The heavy losses and weak tactical positioning prompted the general in command of the Confederate cavalry, John S. Marmaduke, to give up his invasion of Missouri before it could even get underway.

Marmaduke had hoped to attack federal supply routes centered at Cape Girardeau, but he was repulsed and surrounded by Union troops under command of Major General John H. McNeil. Marmaduke ordered Brigadier General M. Jeff Thompson to build a makeshift bridge and ferry to transport his men over the St. Francis River near Chalk Bluff, Arkansas, to escape. It was at the makeshift river crossing that Captain Hulse led his company against Thompson and ended up being captured along with 23 of his men, and he was later exchanged and released to fight again.

Hulse’s letter to his parents described the loss of two of his subordinates who died at Chalk Bluff, writing that, “it was a sad & mournful spectacle to see two of my best men [wrapped] in their Blankets at Chalk Bluff & laid in their final resting place.” What prompted memories of this incident from the year before was the recent loss of one of his men who died from pneumonia. Unlike the two men hastily laid to rest at Chalk Bluff, the recent one could at least be buried in a “respectable coffin” and “with honors of war.”

Hulse had clearly learned the lessons of war as he prepared defenses in May 1864. He described the “horrors of a Southern prison,” including the “Ignorant guards placed over [him].” Even at the town of Dallas, Hulse described a lack of provisions, explaining that “there is nothing in the country to eat” and “there are thousands suffering for the necessaries of life.” Given his company’s experiences, preparedness was of the utmost concern, as he described to his parents: “A burned Child dreads the fire & so with [Company H.,] they once have tasted the bitter fruit of Rebledom & do not intend trying a second [dose] without a Struggle.”

All Quiet in Kansas City

Meanwhile, in Kansas City, the Unionist and Baptist Reverend Jonathan B. Fuller enjoyed a relatively calm respite from the strains of war. As he related in a letter to his father on May 23, 1864, “Things are quiet in a general way. We have bushwhackers in the county—but I think they are few in number and not likely to do any general mischief. I hope they will keep quiet—for my success in building up the church depends in great measure upon it.”

Fuller’s observation about greatly reduced pro-Southern guerrilla activity along the Missouri-Kansas border was undoubtedly accurate. Aside from the deep controversies surrounding several events from the summer of 1863—including the collapse of a prison housing women relatives of known bushwhackers in Kansas City, Quantrill’s Raid on Lawrence, Kansas, and General Order No. 11 in response to that raid—the unusually harsh measures taken by Union authorities against the rural population had at least succeeded in quelling much of the guerrilla violence and reprisals that had plagued the border since the mid-1850s.

The relative calm allowed the citizens of Kansas City an opportunity to resume more ordinary activities, albeit with the shadow of war hanging over them. Fuller would not be directly involved in the war again until later in the year, giving him time to focus on holding his congregation together and attempting to expand it. In his letter, he made a brief reference to his church services being attended by protesting “Campbellites,” who were followers of the reformists Thomas and Alexander Campbell. The Campbells led the Disciples of Christ movement, which wanted to follow a more literal or “primitive” interpretation of the New Testament, including the rejection of such practices as having musical instruments in church service. Fuller described their impact on his service as minimal, though, and he was mostly pleased with the attendance that filled three-quarters of the building.

On the previous Saturday, Fuller attended and spoke at a school picnic where the “Queen of the May” was presented. He was also planning to attend a picnic the following Saturday for his Sunday school, and he related an ongoing joke within his congregation about his physical attractiveness. All the while, he described a backdrop of unusually dry and hot weather, which made for dusty roads and dry vegetation.

But the Civil War was never far from anyone’s mind. At the picnic, Fuller led a prayer for the “strong men [who] were going out in battles wild rage to the warriors bloody doom—and while we with garlands crowned were meeting in joyous festal—pain and woe mutterable were darkening many a heart and home.” Furthermore, Fuller speculated on national events by referencing the beginning of General Ulysses S. Grant’s Overland Campaign, which began with the Battle of the Wilderness and the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House between May 5 and May 21, 1864.

While historians recall Grant’s campaign as one that ground down General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia through battles of attrition, many Northern citizens were shocked and outraged at the huge number of casualties Grant was willing to accept in order to push Lee’s army to the brink of dissolution. In the first two weeks alone, Grant’s Army of the Potomac lost 36,000 soldiers to death, wounds, desertion, or capture, and speculation was rampant that President Lincoln would lose his upcoming campaign for reelection in November.

Writing in Kansas City in late May, Reverend Fuller could only comment that “News from the Potomac is not quite so encouraging as I could wish. But as Grant’s military renown is at stake, I am confident that Lee will have to stand a severe tug before the matter ends.” It would be another 11 months before General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox.

Anticipating Another Destructive Summer

Like Reverend Fuller, other Missouri residents could not overlook the sense of foreboding that came with the fourth spring season of the war. Writing to his fiancé from Calhoun, Missouri, the merchant and Unionist John A. Bushnell continued to live in fear of violence from pro-Southern bushwhackers and even referenced rumors of a large-scale invasion of Missouri being prepared in Arkansas.

As typical of Bushnell’s correspondence, he shared his extensive contemplations about religion and the war, on this occasion writing about “whether God had any thing to do with the war?” “Most surely,” Bushnell wrote, “He has a wise purpose in all this.” He went on to speculate about the war being a punishment for sins and wondered if famine and disease would follow the war’s end. He seems to stop just short of speculating that the coming of the millennium in the next century would fulfill the Book of Revelation and that the end times were being ushered in.

Bushnell continued the letter on the next day, May 17, in a less philosophical and more practical mood. He mentioned declining an invitation to go fishing and wrote that he would like to go fishing and also take a picnic, “but as times are I guess we will have to put it off for better times, when troubles or dread will not mar pleasure.” For years Bushnell had been cautious about bushwhackers, and this letter gives no indication that he had taken any risks of straying away from town or visiting his fiancé, Eugenia Bronaugh, in Hickory Grove, Missouri. Referencing the bushwhackers, he went on to warn her that she should “be careful, you know what the penalty is and what joy some of your neighbors would have to get a chance to burn your house & destroy your farm, so do not lay yourselves liable.”

View Shelby's Raid in a larger map

More interesting is that as early as May 1864, rumors were starting to circulate about a possible invasion of Missouri. Bushnell had heard that General Marmaduke was already leading an expedition of 30,000 men into the state, with General Sterling “Old Pap” Price preparing an additional 60,000 men. Bushnell recognized that a combined force of 90,000 soldiers invading from Arkansas would have been a completely unrealistic figure, adding that “this we know is not so [but] I shall look for the papers this evening with great interest.”

An invasion force of 90,000 never emerged, of course, but Bushnell and his fellow Missourians did have sound reasons to be concerned about a large raid taking shape over the summer and fall. The previous year from September 22 to November 3, 1863, Colonel Joseph “Jo” Shelby led “Shelby’s Great Raid” into Missouri, disrupted Union Army operations in the state, and caused heavy property damage in towns including Boonville, Warsaw, Tipton, Stockton, and Neosho. The next year, on September 19, 1864, General Price led an invasion with the Army of Missouri (consisting of 12,000 cavalry men and aided by Generals Marmaduke, Shelby, and James F. Fagan) across the Arkansas-Missouri border on what would end up being the largest cavalry raid of the war.

Even if their calculations were wildly inaccurate, Missouri citizens, including John A. Bushnell, were wise to prepare for the possibility of such an invasion by Sterling Price.