Reproduction of barracks for prisoners of war outside of Fort Delaware. Image courtesy of Flickr user combatphoto44.

By Jason Roe, Kansas City Public Library

Each month in 2014, the Library will commemorate the sesquicentennial of the Civil War in Missouri and Kansas with a post derived from the thousands of primary sources that are digitized and incorporated into this website. The Library and its project partners collaborated to assemble this rich repository from the collections of 25 area archives, combining it with interpretive tools and original scholarship produced by nationally recognized historians.

Coping on the Home Front

For Alex M. Bedford (a Missourian and Confederate soldier imprisoned in barracks outside of Fort Delaware off the coast of the state of Delaware), being captured and removed from the fighting for the rest of the war did not signal the end of his wartime experience or the struggles of his family. In a letter from June 12, 1864, his wife, Mary E. Bedford, wrote to her husband with details about how she and their children were coping on their farm near Savannah, Missouri, about 15 miles north of St. Joseph.

Besides being separated from her husband, who had joined the Southern cause early in the war and been captured in Arkansas in August 1863, Mary Bedford faced the concurrent struggles of maintaining a tenant on their farm, raising their children, coping with the loss of property to federal confiscations, and trying to send provisions, money, and clothing to her husband, whose health began to fail from the conditions of his prolonged imprisonment.

By June 1864, Mary had endured nearly three years in her husband’s absence. Her concerns for the summer centered on the farm, which she rented out to a tenant. In a letter from May, she expressed concerns about the tenant, writing that “he has not planted any corn yet,” and “I am fearful we will have [trouble] with him but I hope we will not.” But in June, Mary reported that “my tenant is doing better Since he found out he could not get me a way.” Still, she seemed frustrated, adding that “I will try to get a long with him in peace,” and “I will never rent our farm a gain[.] I had better let it grow up in weeds.”

In other local news to her husband, Mary wrote that “Mr. Leneer was Shot in Savannah friday for burning the [railroad bridge].” Given the time frame in which she stated that Leneer had been imprisoned for “over two years,” it is quite possible that Mary’s statement referenced an incident from September 3, 1861, in which pro-Southern Missouri “bushwhackers” burned the lower sections of the Platte River Bridge, causing it to collapse at 11:15 p.m. as a train crossed on its way from Hannibal to St. Joseph. One-hundred passengers, including civilians and soldiers, were injured, and between 17 and 20 were killed. The lead bushwhacker who fell under suspicion, Silas M. Gordon, eluded capture, but the tragedy had longer term consequences for several other suspected bushwhackers and the nearby town of Platte City. Believing that Gordon sought refuge in the town, Union forces burnt Platte City to the ground on December 16, 1861, and again in July 1864, but Gordon still avoided capture.

Read an essay by Dr. Jeremy Neely, from Missouri State University, about the Guerrilla Struggle along the Missouri-Kansas Border.Besides noting the friends or fellow Southern sympathizers killed as a result of the war, Mary seemed relieved to report that a relative paid $90 to a creditor, and the creditor effectively wrote off their remaining debt so that Alex would not have to worry about paying the rest. It is remarkable to consider that while Mary and Alex limped along with assistance from relatives and friends, Mary also had to cope with the unfavorable condition of being a known spouse of a Confederate soldier in a Union-controlled state. In September 1863, for example, Alex learned that their horse had been confiscated by federal soldiers as “contraband property.” Moreover, Alex expressed concern in several letters that if he took a loyalty oath and secured a release from prison, he would be vulnerable to attack from Unionists upon returning home.

Meanwhile, Alex suffered a fate common to prisoners of war during the Civil War. Mary mentioned sending him a pair of socks, “a pair of drawers I had on hand & 8 pounds of butter.” Additionally, she relayed that she gave “Mr. Bohart Money to [buy] you a Shirt & ten paper collars.” Despite the regular mailing of provisions, though, Alex continued to suffer as the War Department reduced rations to its prisoners in 1864 in response to the rapidly deteriorating conditions for the Union soldiers imprisoned in Confederate camps. While prisoners could continue to receive packages from loved ones and purchase extra food, by the beginning of 1865 Alex would write to Mary that, “I must get out of prison or I will soon go to my long home[.] I am leaner in flesh than I ever was[,] would weight a bout 155[,] my usual weight from 165 to 180[.] I am so weak I reel as I walk & nearly lossed my eyesight.”

Fog of War

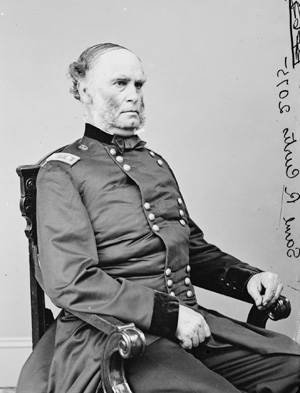

During June 1864, wartime circumstances forced another Missourian named Eugenia Bronaugh to be separated from her fiancé, John A. Bushnell, and she showed concern over his eyesight and physical safety in the climate of guerrilla violence that characterized the state during the Civil War. Their correspondence from June, along with telegrams and letters from General Samuel R. Curtis and a captain from the 11th Kansas Cavalry, demonstrate the paucity of information available to civilians and military commanders, the fear that such uncertainty caused, and the consequent disruption of federal strategy in the area.

Bronaugh had an ongoing concern about Bushnell’s failing eyesight, particularly because, in her words on June 10, “I well know your great love of reading, & I fear you have used your eye entirely too much, as well as have exposed it to the light, when you should have been in a dark room.” But the correspondence between the couple revealed the necessity of reading the latest news and trying to determine the current threat from bushwhacker violence. As a known Unionist, Bushnell often feared an attack from pro-Southern bushwhackers if he visited Bronaugh in Hickory Grove in the eastern part of Missouri, where she lived with her family.

Bushnell, a merchant from the town of Calhoun in the western part of the state, occasionally visited his fiancé, but he always exercised caution about the timing of his visits and clamored for the latest news about guerrilla activity. Bronaugh likewise complained throughout her June letter about the lack of accurate information available, particularly in the rural town of Hickory Grove. Regarding a potential visit, she advised Bushnell that he “can be a better judge than us, for we hear comparatively little that goes on in this neighborhood or else where. Perhaps you can hear more, & I only want you to do what you deem prudent & safe.”

Bronaugh and Bushnell’s desire for accurate (or comforting) news extended to rank-and-file soldiers and generals alike. On June 7, Major General Samuel R. Curtis sent a telegram from Fort Leavenworth to the governor of Kansas, Thomas Carney, updating him that he had issued arms and ammunition, but offering no more details beyond the vague statement that “Bushwhackers are east & south of us and hostile thieving Indians west.”

The ambiguity of Curtis’s statement was reflected in several other telegrams and letters that relayed reports of hundreds of Missouri bushwhackers preparing to stage attacks in Kansas, as the guerrilla leader William Clarke Quantrill had done the previous fall in a devastating raid on the civilian population of Lawrence, Kansas. Following Quantrill’s Raid, the Union issued the controversial General Order No. 11, depopulating the rural civilian population of four western Missouri counties and undermining the base of support for bushwhackers planning attacks over the border into Kansas.

Nonetheless, Edmund G. Ross, a captain in the 11th Kansas Cavalry, wrote to his wife from Olathe, Kansas, that “Reports are rife of hundreds of bushwhackers just over the line, & the troops are on the constant move.” Ross was likely relaying information from a separate telegram from General Curtis, which reported that between 150 and 200 Missouri guerrillas were staging an attack on Olathe, Lawrence, and Topeka. Another telegram received by Captain Ross reported that 350 cavalry had been moved from Kansas City to Olathe to intercept the guerrillas.

While modern observers may dismiss these various communications as the result of rumors and paranoia rather than substantiated facts about guerrilla activity, their concern was well-warranted considering the previous years of irregular warfare that characterized the Missouri-Kansas border. The correspondence also revealed that by continuing to spread fear, the bushwhackers were accomplishing one of their primary goals – to distract and drain resources from the federal forces who were forced to pursue unseen threats rather than go on the offensive against the regular Confederate military.

Walking a Thin Line

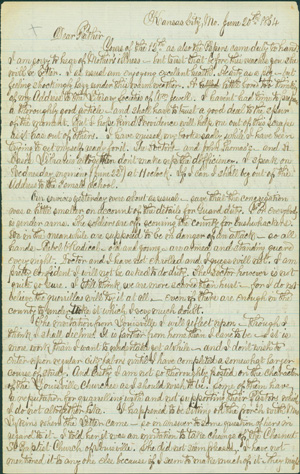

At least one individual in the region remained unconcerned about the bushwhacker presence. In a letter sent from his home in Kansas City to his father on June 13, Reverend Jonathan B. Fuller responded to the circulating rumors of bushwhacker activity: “Bushwhackers are I suppose in the county – but I am inclined to think their number sadly exaggerated.” In a second letter from June 20, 1864, Fuller continued to dismiss the bushwhackers, writing, “I still think we are more scared than hurt—for I do not believe the guerrillas will try it [an attack] at all—even if there are enough in the county to undertake it which I very much doubt.” Instead, Fuller concerned himself with a more personally pressing issue, keeping his Baptist congregation from splintering over political divisions and violence.

In his June 20th letter to his father, Reverend Fuller elaborated on the problems in his congregation, writing that he was “looking for an explosion any moment.” He related two incidents from the previous 10 days, both of which involved Unionists pushing for war-related propaganda during church services. In the first instance, an individual asked Fuller to read out a recruiting notice in church. Although a staunch Unionist himself, Fuller considered the request unnecessary because it had already been published in the morning paper and was “inappropriate for church.” His refusal to make the announcement apparently ruffled feathers among the most vocal Unionists in his congregation.

In the second incident, the leader of the choir, “a regular down east Yankee,” wanted to sing the patriotic song, “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee” during church services. Fuller heard of the plan on the Saturday before the service, giving him time to ponder the issue. Describing his reasoning to his father, Fuller wrote,

It was a delicate question. If the hymn was sung the Rebels and "softs" generally might regard it as an insult to their sensibilities and withdraw from the congregation, if on the other hand I should suppress the piece--the Radicals of the Methodist Church might get hold of it and use it against me. Very providentially the leader came late that morning--and I gave out the regular hymn before he got in.

The incident demonstrates the thin line Fuller had to walk to keep his services apolitical with a congregation made up of “radical” Unionists who wanted to abolish slavery in Missouri immediately, conservative Unionists who thought it was safest to prolong slavery in the border states, and even secessionists or those in favor of a negotiated peace settlement. The conservatives considered the radicals to be overly concerned about the plight of African Americans, to the detriment of the slave states that remained in the Union, whereas the radicals believed that the conservatives were disloyal Southern sympathizers.

The dispute between radical and conservative Unionists grew so intense by the spring and summer of 1864 that many Missourians feared an additional outbreak of hostilities between those factions. In his own case, Reverend Fuller feared losing the radicals to the more outspokenly progressive Methodist Church or losing conservatives and secessionists by giving the radicals too much hold on the pulpit. All the while, guerrilla attacks or federal suppression of the pro-Southern population threatened to spark spontaneous violence between the two sides.

Learn more about the refusal of some Missouri citizens to take Loyalty Oaths, an essay by Dr. Christopher Phillips, University of Cincinnati.Throughout the war, Fuller maintained neutral leadership by skillfully strategizing like a politician and buffering his position with well-regarded friends on both sides of the conflict. His correspondence reveals that he befriended the family of Dr. Johnston Lykins (Kansas City’s second mayor), and Dr. Theodore S. Case, an outspoken Republican who nonetheless supported the mayoral candidacy of the anti-secession Democrat, Robert T. Van Horn. As mayor, Van Horn went on to guide the city’s defense efforts and was widely credited with keeping Kansas City under Union control in the early weeks of the war. While Fuller’s friend, Dr. Lykins, remained loyal to the Union, it is important to note that Fuller also continued a friendship with Lykins’s second wife, Martha “Mattie” Lykins, a Southern sympathizer who had to move from Kansas City to Liberty, Missouri, because she refused to take a loyalty oath after the issuance of General Order No. 11 the previous fall.

A third connection who aided Fuller was someone he referred to as “Bro. Rogers . . . one of the blackest Radicals in town.” In both of the incidents recounted above, Fuller sought Rogers’s support so that the radical Unionists could not complain too much. As Fuller explained to his father, “as long as I can keep him between me and the Radical [line] I am safe I think in that quarter.”

Despite his best efforts, though, the stability of Reverend Jonathan Fuller’s congregation would remain in doubt as he entered the second half of 1864.