A 36 star American flag used sometime between the admission of Nevada in October 1864 and 1867. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

By Jason Roe, Kansas City Public Library

Each month in 2014, the Library will commemorate the sesquicentennial of the Civil War in Missouri and Kansas with a post derived from the thousands of primary sources that are digitized and incorporated into this website. The Library and its project partners collaborated to assemble this rich repository from the collections of 25 area archives, combining it with interpretive tools and original scholarship produced by nationally recognized historians.

Independence Day, North and South

At the beginning of July each year, Northerners and Southerners had an annual occasion to pause and reflect on their respective understandings of patriotism and the meaning of the Civil War. For Unionists, including one Missouri resident who wrote to his fiancé on July 3, 1864, the patriotic celebration of Independence Day reaffirmed the themes of a united nation, a free population, and the federal government that had emerged out of the American Revolution. Most Confederates, though, were not prepared to abandon the holiday to the North with the onset of the Civil War. They instead preferred to stress that their rebellion was justified by the Declaration of Independence, because they believed they were fighting against an unjust government that impinged on their property rights and failed to represent their interests.

Citing his desire for "a happy and peaceful Country—‘the land of the free and the home of the brave,’" John A. Bushnell, a Unionist resident of Clinton, Missouri, and himself a former slaveholder, described his hope that the patriotism surrounding the Fourth of July would make Southern sympathizers reevaluate their stance. Bushnell hoped that the words of Thomas Jefferson would,

come down like the Power of the Holy Ghost—until not a traitorous feeling is left, until all shall realize that this dwelling place was not made by selfish, for selfish purposes but for the Everlasting good—the benefit of all who can appreciate its blessings and live evangelic—true to its teachings.

As for the celebrations themselves, he wrote that, "great preparations have, I understand, been made, and the usual forms will be gone through with." After the Fourth of July, Bushnell summarized that the Declaration of Independence was read publicly, and a minister followed with a speech, "conclusively, in his own mind, proving the races equal...." Even if Bushnell (who had possessed his own slaves less than a year before) did not personally agree with the message of racial equality, he related that the assembled crowd made no protests against the message, nor was anyone surprised by it.

Bushnell’s description of traditional celebrations applied to much of the North, but for pro-Southerners, the celebrations were far from routine. Each year, Southerners reconsidered the meaning of the holiday in a process which proved to be more complicated as the war continued and the Confederacy’s position deteriorated. Historians including Drew Gilpin Faust, Anne Sarah Rubin, and others have argued that the Confederacy retained many of the foundational traditions of the United States for purposes of continuity. By upholding celebrations of the Fourth of July, Southerners could claim that their own revolution was a continuation of the principles inherent in the American Revolution, with the Confederacy serving as its new standard bearer.

Read excerpts from Mississippi and Alabama’s declarations of secession, which laid out their justifications for joining the Confederacy and served a similar purpose as the Declaration of Independence in the American Revolution.Professor Paul Quigley, whose research examines Southern nationalism in the mid-19th century, argues in The Journal of Southern History that the Revolution also left a problematic legacy for the Confederate states. In the decades leading up to the Civil War, Northern abolitionists marked the holiday with appeals to the concept of equal rights enshrined in the Declaration of Independence. Other reformers in the North and South stressed the importance of temperance, women’s rights, religious observances, and morality to the continued wellbeing of the nation. By the 1850s, according to Quigley, the abolitionists had succeeded in linking their cause of racial equality with the Fourth of July to such an extent that newspapers remarked on how muted the celebrations had become throughout the South.

As Quigley explains in his article, with the beginning of the Civil War in 1861, Southern groups including the ’76 Association in Charleston, South Carolina, had to grapple with how to emphasize the Americanism of the Confederate cause while also drawing sharp contrasts with what had increasingly become a Northern celebration of unionism and equal rights each July. That commemorative organization and others across the South decided to abandon traditional celebrations for the duration of the war, but they maintained their claim to the "constitutional principles" of the holiday.

Although many Southerners continued to mark Independence Day as an important—if somewhat somber—occasion, Unionists such as John A. Bushnell found good reasons to continue celebrating the Fourth of July in the traditional manner. For Northerners it served as a patriotic rallying cry on behalf of national traditions and unionism, whereas for Confederates by 1864, it served as a reminder that their own national experiment was still struggling for survival and independence.

Bushwhacker Leadership in New Hands

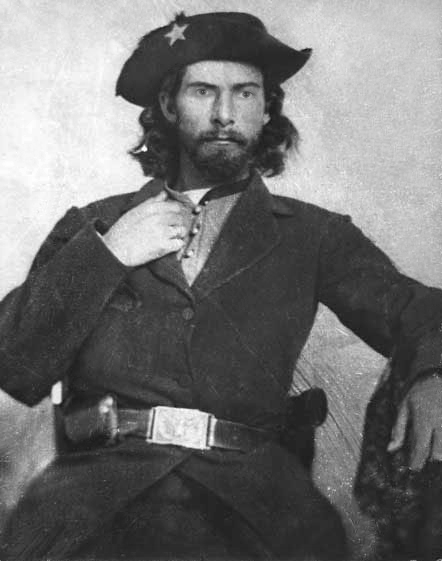

In Missouri, the Confederate cause fell into the hands of guerrilla bands that, despite fractured leadership and mounting fatigue, managed to continue disrupting federal military operations and pave the way for an immense Confederate cavalry raid from Arkansas. By July 1864, rumors of Major General Sterling Price organizing a cavalry force in Arkansas had been circulating freely for months, and Missouri residents on both sides of the conflict anticipated that the raiders might enter the southern part of the state at any time. Unionists were also concerned about the numerous reported sightings of the infamous bushwhacker William Clarke Quantrill, who was supposedly leading his band of guerrillas, known as "Quantrill’s Raiders," against civilian and military targets. What the Unionists did not know was that even as guerrilla activity escalated in July, there was no longer a need to be concerned about Quantrill specifically.

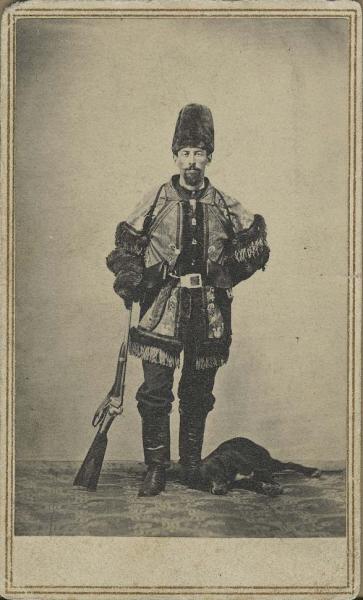

On July 22, a federal soldier named Lewis A. Waterman wrote from Fort Leavenworth to his mother, describing a force of 500 men led by Quantrill capturing "several places." In an apparent retaliation, Colonel Charles R. Jennison led some 700 men into Missouri and, according to Waterman, killed 150 bushwhackers with a loss of only two. The numbers listed by Waterman were likely wildly exaggerated, but they hinted at the brutal retributions against the bushwhackers that made "Jennison’s Jayhawkers" (the 7th Kansas Volunteer Cavalry), notorious along the Missouri-Kansas border. As the Kansas counterpart to Missouri bushwhackers, "jayhawker" units such as Jennison’s often operated as an official part of the U.S. Army, but without formal sanction for their more extreme activities. By the time of Quantrill’s devastating raid on Lawrence, Kansas, on August 21, 1863, Jennison had already resigned unceremoniously and began to lead an unofficial "Red Leg" militia, which gained a reputation for indiscriminately targeting and killing Missouri residents and plundering their belongings. After Quantrill’s Raid, Kansas Governor Thomas Carney reinstated Jennison as a state militia colonel.

Jennison’s operations may have harassed some bushwhackers and their supporters, but by July 1864, Quantrill was no longer operating in the areas that Jennison targeted, or anywhere at all, for that matter. The fall from grace of Quantrill’s Raiders, as documented by Donald Gilmore and other historians, happened quickly. After Lawrence, Quantrill commanded 400 bushwhackers in a victory against Major General James G. Blunt outside of Baxter Springs, Kansas, proving that the guerrillas could win an engagement against a regular Union force. After these triumphs, however, Quantrill’s Raiders wintered in Texas, where their lawless reputation preceded them. Quantrill’s men succumbed to infighting as one faction (led by William T. "Bloody Bill" Anderson and Fletch Taylor) blamed another (headed by George Todd), for hoarding the loot taken from Lawrence. Amidst the malcontent, a faction of the guerrillas raided the town of Sherman, Texas, on Christmas Day, 1863, and in related antics to the south of town, killed a Confederate colonel and a major.

Confederate General Ben McCulloch, probably already seeking a way to distance the Confederacy from Quantrill’s undignified reputation, issued a warrant for his arrest. Soon escaping from prison, Quantrill, Todd and their followers fled, while Anderson commanded a somewhat larger portion of the bushwhackers. Amid the breakup of the guerrilla band, Quantrill’s remaining followers elected George Todd as their new captain. Quantrill, who had once been recognized officially at the rank of captain in the Confederate Army under the Partisan Ranger Act of 1862, and who vainly claimed the higher rank of colonel, was left without a command and with an outstanding warrant for his arrest.

None of this stopped the now-splintered bushwhackers from continuing their attacks. A Missouri resident from Maryville wrote to his son and described the situation: "In all the counties, below this, there are Bushwhackers[,] Rebels, raids[,] fights, and also individual shooting, & men killed in all directions. The Rebels of this County have been indicted for Treason, and there will be extensive trials." On July 6, Todd encountered a company of Union cavalry somewhere between Independence and Pleasant Hill and left seven Union soldiers dead. On July 10, a guerrilla group consisting in part of five companies of so-called "Paw Paw" militia (made up of men who had been hastily armed and incorporated into the Union’s Missouri state militia despite a previous record of disloyalty) rose up and claimed Platte City, already known as a secessionist bastion, for the Confederacy.

Read more about the guerrilla struggle on the Missouri-Kansas Border in an essay by Dr. Jeremy Neely.The Union retaliation was swift, as on July 13 nearly 1,000 cavalry commanded by Colonel James H. Ford reclaimed Platte City, killing several dozen bushwhackers—possibly including unaffiliated civilians and definitely including some who were taken prisoner and shot without trial or court martial. The federal force then burnt Platte City to the ground, sparing only a church building in the center of town, and looted hundreds of horses and additional provisions. Reverend Jonathan B. Fuller, writing to his father from Kansas City on July 18, described seeing a Union force depart over the river headed north, adding that, "Some say that Platte City[,] some twenty five miles above has been burned to the ground by our soldiers—others say it has been only partially destroyed[.] I think the latter supposition the most probable."

Despite the fading away of William Clarke Quantrill, bushwhackers led by "Bloody Bill" Anderson, George Todd, and others continued to distract or harass Union forces in Missouri as the summer of 1864 commenced. Rather than being able to take the offensive against the Confederacy in the West, the Union was still fighting to retain control over the state of Missouri, and in August 1864, Confederate Major General Sterling Price would finally begin preparations for his long-rumored invasion of the state.

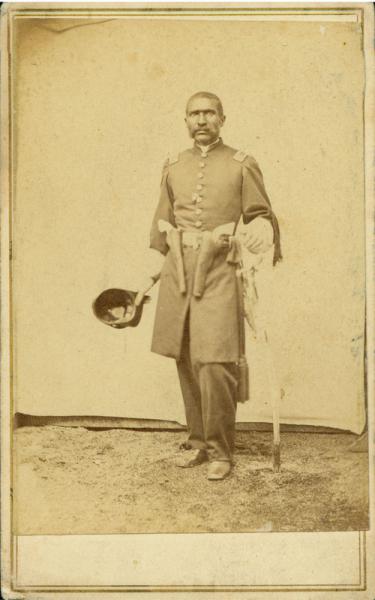

Black Soldiers Receive Equal Pay

Implementation of a major shift in Union military policy also began in July 1864. In June the U.S. Congress passed a law granting equal pay to African American soldiers, and in July the military began implementing the changes. Writing from St. Louis, Missouri, on July 18, Colonel E.B. Alexander officially informed Captain William Fowler, the provost marshal for the 7th District of Missouri, of the new law, "allowing Colored troops the same pay bounties as whites."

The discrepancy in pay between black and white soldiers during the Civil War dated back to their initial enlistment, which, although originating with the Militia Act of 1862, was formalized with the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. The intention of the Militia Act was to enlist blacks as laborers only, at a rate of pay significantly lower than white soldiers. But as early as August 1863, one month after the Militia Act passed, segregated black regiments, including the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteers, formed. In the case of the 1st Kansas, Brigadier General and Senator James H. Lane raised the regiment by listing the new recruits as mere "laborers." On October 29, they became the first black unit to engage the enemy in the successful Battle of Island Mound in Bates County, Missouri.

Black soldiers fought in large part against slavery and so that no one could deny that as a people they had earned equal civil rights with the white population. They received encouragement to fight from such prominent individuals as the abolitionist John Brown (prior to his death at the gallows in December 1859) and the self-educated former slave Frederick Douglass (who sent two of his own sons to fight in the war). Additionally, blacks had fought in the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, and black women contributed to the war effort in non-combat roles. By the end of the war, black soldiers made up some 10 percent of the Union Army’s enlistees.

The irony of fighting against slavery on the side of a nation that continued to pay its black soldiers substantially less than its white soldiers did not escape the men who were laying their lives on the line for their cause. In 1864, freshly recruited white soldiers received $13 a month, while black enlistees received just $10 based on a laborer’s pay under the Militia Act of 1862. Still worse, only black soldiers had to pay an additional $3 per month for clothing, making their actual pay only $7. Famously, the rank and file of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry elected to decline the entirety of their wages while continuing to fight. Even after the state of Massachusetts offered to pay the difference in wages for the 54th Massachusetts, they declined based on principal.

In June 1864, Congress finally reversed the policy, equalizing pay and eliminating the extra clothing fees. Additionally, Congress made the legislation retroactive to January 1, 1864, or even earlier to the time of enlistment for any black soldiers who were already free upon enlisting in the army. Due to poor record-keeping, it is believed that many blacks who enlisted from border states like Missouri and Kentucky while still slaves were also granted the more generous terms of retroactive pay accorded to their fellow freedmen.

Learn more about African American soldiers in the Civil War from the National Archives website.Back in Missouri, other implications of the legislation began to emerge in July. The same letter from Colonel E.B. Alexander stated that the black soldiers "may therefore be accepted as substitutes for whites." In both the Union and the Confederacy, numerous exemptions were made in the draft policies. On the Union side, the most notable was that if drafted, a healthy male citizen between the ages of 20 and 45 could avoid service by either paying $300 or finding a suitable substitute, possibly by hiring the substitute to take his place. For better or worse, blacks could now serve as substitutes for white draftees, placing them on a more equal footing in terms of federal draft policy. Considering that the draft initially excluded African Americans altogether, because they were not considered citizens, the new substitution policies could be seen as additional, if limited, progress toward full citizenship rights.

The men and families associated with the 1st Kansas, and all other African Americans nationally, would have to wait until the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments between 1865 and 1870 to receive the universal rights for which they fought, and still longer for the reforms of the Civil Rights Movement in the mid-20th century. In the month of July 1864, though, black soldiers could at least find solace in substantially higher wages and a certain degree of respect earned from their new reputation as fearsome fighters.