By Matthew E. Stanley, Albany State University

Biographical Information:

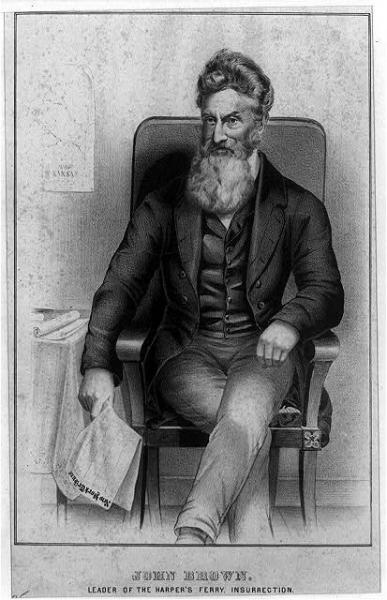

- Date of birth: May 9, 1800

- Place of birth: Torrington, Connecticut

- Claim to fame: Radical abolitionist; led Pottawatomie Massacre; attacked Harpers Ferry

- Nickname: "Osawatomie Brown"

- Date of death: December 2, 1859

- Place of death: Charles Town, Virginia

- Cause of death: Hanged for his attack on Harpers Ferry

- Final resting place: John Brown Farm Grounds, North Elba, New York

John Brown was an American abolitionist who believed in using violent methods to eradicate slavery in the United States. He is most famous for leading an attack on a federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia), in 1859. Although unsuccessful in his aim of overthrowing slavery in the American South, Brown’s raid and his subsequent execution fueled tensions in the national debate over slavery in the United States. Historians credit Brown, his raid, and the public debates surrounding his trial and legacy with hastening Southern secession and the Civil War.

Brown became convinced that only violence was sufficient to quell the proslavery faction and bring Kansas into the Union as a free state.

Brown was born on May 9, 1800, in Torrington, Connecticut and was raised in an evangelical family in Ohio’s Western Reserve. Brown was twice married and had 20 children between his two marriages. He engaged in a number of occupations between 1820 and 1855, including tanning, the livestock trade, and surveying. Brown grew increasingly antislavery upon moving to Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1846. There he met the famed abolitionist and escaped slave Frederick Douglass, became familiar with the Underground Railroad, and founded the League of Gileadites (a militant group determined to prevent the capture of runaway slaves) in response to the Fugitive Slave Act. This radicalization led Brown to join his sons in the Kansas Territory in 1855.

Driven by both local and national disputes over the slavery issue, Brown became convinced that only violence was sufficient to quell the proslavery faction and bring Kansas into the Union as a free state. On May 24, 1856, Brown, three associates, and five of his sons attacked proslavery settlers, during which five proslavery men were killed with broadswords in what became known as the Pottawatomie Massacre. Brown and a band of followers went on to defeat proslavery forces at the Battle of Black Jack in June 1856.

Brown also helped defend the Free-State settlement of Osawatomie in August 1856, a fight in which his son, Frederick, was killed. Brown returned east in late 1856 to raise funds for his antislavery activities and garner the support of prominent abolitionists, including six benefactors that became known as the Secret Six. It was during this time that Brown first articulated his planned slave insurrection and invasion of the South.

Be sure to watch John Brown brought to life in an event at the Kansas City Public Library!

Planning to seize weapons to arm local slaves, Brown and 18 followers attacked the Harpers Ferry Arsenal on the night of October 16, 1859. Brown took several prisoners, and by the next morning locals and the militia had trapped the raiders in the arsenal’s engine house, which became known as John Brown’s Fort. U.S. Marines commanded by Colonel Robert E. Lee raided the engine house on the morning of October 18, killing 10 of Brown’s raiders, including two of his sons.

Old John Brown’s body lies moldering in the grave,

While weep the sons of bondage whom he ventured all to save;

But tho he lost his life while struggling for the slave,

His soul is marching on.

John Brown was a hero, undaunted, true and brave,

And Kansas knows his valor when he fought her rights to save;

Now, tho the grass grows green above his grave,

His soul is marching on.

Brown was tried by the state of Virginia and on November 2 found guilty of treason. The trial polarized the nation, revealing the mounting sectional tensions between North and South. Brown refused a rescue attempt and instead used correspondence to cultivate his image as an abolitionist martyr in the Northern newspapers.

Brown was hanged on December 2, 1859, in Charles Town, Virginia (now West Virginia) and buried on his farm in North Elba, New York. He continued to live in the nation’s memory, though. Union soldiers sung “John Brown’s Body,” which featured some variation of the lyrics, “John Brown’s body lies a-mouldering in the grave; his soul is marching on.” Later, Julia Ward Howe wrote new lyrics for the song in 1861, and it became, “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

John Brown remains a highly controversial figure among scholars and in the public imagination. Although writers after Reconstruction and during the Jim Crow era often viewed Brown as insane, post-Civil Rights Movement historians have depicted Brown in a more sympathetic light, a position previously held primarily by black scholars. His legacy among the general public continues to range from that of a martyr and early civil rights icon to a terrorist or a mentally ill criminal.

Suggested Reading:

Gilpin, R. Blakeslee, ed. John Brown Still Lives!: America's Long Reckoning with Violence, Equality, & Change. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

Oates, Stephen. To Purge This Land with Blood. Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1970.

Reynolds, David S. John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005.

Cite This Page:

Stanley, Matthew. "Brown, John" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Tuesday, July 2, 2024 - 22:30 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/encyclopedia/brown-john