Summary:

- Type: Two broadsides

- Date: August 2-7, 1854; August 12, 1854

- Authors: Benjamin F. Stringfellow and H. Miles Moore

- Significance: Stringfellow and Moore debate their proslavery and antislavery views

- Owning Organization: State Historical Society of Missouri - Columbia

- Related History: Bleeding Kansas; Free-State Party; Border Ruffians

By Jason Roe, Kansas City Public Library

The Featured Document Blog places the past in your grasp by introducing a compelling item from our digital collection.

These two broadsides, owned by the State Historical Society of Missouri-Columbia, date from August 1854 and document a heated personal and political grudge between the proslavery Benjamin F. Stringfellow and H. Miles Moore, who would come to side with the antislavery cause and fight for the Union in the Civil War. Despite widespread 21st century complaints about “dirty politics,” modern political disputes have, to date, been considerably milder than their counterparts in the antebellum period, when such arguments not infrequently escalated from cutting personal insults into actual duels. The “Bleeding Kansas” violence that resulted from the debate over whether Kansas Territory would enter the Union as a free or slave state even extended to the U.S. Senate chambers, where Representative Preston Brooks caned Senator Charles Sumner to the brink of death.

A similar grudge played out between Benjamin F. Stringfellow and H. Miles Moore in the area of Leavenworth, Kansas, and Platte City, Missouri. Moore publicly accused Stringfellow of saying in a public speech, that “all who labor for their daily bread . . . are slaves” and “all females who labor for their daily bread are whores.”

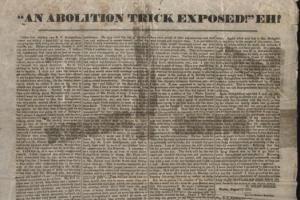

The First Broadside: “An Abolition Trick Exposed!”

Stringfellow was a staunch proslavery advocate and a leader of the Platte County Self-Defensive Association, a militia group of Missouri border ruffians who opposed the settlement of Free-Staters across the border in Kansas. His broadside, the first of the two documents highlighted in this blog, denounced Moore’s accusation. Stringfellow denounced the accusation that he saw laboring white men and women as the equals of slaves, writing,

I do not believe that the white man or the white woman is fitted for slavery – was ever intended for slavery! I prefer seeing the white man free – the negro a slave. . . If any white man or white woman wish to be a slave they must not ask me to be their master. It is too repulsive to my nature!

Stringfellow continued to state that the most impoverished free white laborer is “entitled to such respect, to such privileges” that no servant or slave deserves. Throughout the document, Stringfellow accused Moore (who then claimed to be neither abolitionist or proslavery) of being a radical abolitionist who wanted to destroy the economic and God-given moral hierarchy of slavery.

Finally, toward the end of the broadside, Stringfellow attacked Moore’s masculinity by writing,

I say to you white working women if your husbands admit that they sat silent and heard your good name slandered as Moore and his witnesses debase themselves by admitting they understood me to slander you—and did not on the spot indignantly repel the slander—kick them from your beds! Abandon them . . . . with such fathers your children may be slaves!

The Second Broadside: “‘An Abolition Trick Exposed!’ Eh?”

Moore’s response can be read in his own broadside, headlined “‘An Abolition Trick Exposed!’ Eh?” Moore reaffirmed his accusations against Stringfellow’s speech, and stated that Stringfellow and his men confronted him “with revolvers and bowie-knives,” thereby making it futile to physically assault Stringfellow for his slanders against working women.

Addressing white laborers directly, Moore explained that Stringellow did indeed say that they were slaves:

If you poor men are free-soilers, and if all are freesoilers that employ white men to work for them—and he [Stringfellow] says it is slavery to work for your daily bread—why then, all who employ white men must be slaveholders and those of you who labor must be slaves.

Moore, who had himself once been a slaveholder, was no abolitionist, and in the broadside he denied being a Free-Stater as well (although within a year he was a delegate to the Free-State Topeka Constitutional Convention in 1855 and became the territory’s attorney general under that contested constitution.) He displayed ample disregard for black men and women, but he also attacked Stringfellow’s staunch proslavery views that he feared could lead to the dissolution of the Union, which he referred to as a “confederacy” in the following statement:

While I condemn and despise an abolitionist as the most contemptible of the human family, I have an equal contempt for a low-flung, red-mouthed fire-eater, who has the utter destruction and ruin of our Glorious Confederacy at heart.

The term “fire-eater” referred to the most extreme proslavery Southern Democrats who feared that Northerners would ban slavery throughout the nation, thus destroying the economic and social basis of Southern society.

Among the many additional insults H. Miles Moore slung at Stringfellow was the phrase, “contemptible vagabond,” but the most interesting historical matter lies in unraveling Moore’s confused stances on slavery, abolitionism, race, the Free-Soil movement, gender, and class. At the time these broadsides were distributed in 1854, he was still transitioning from being a Louisiana slaveholder as recently as 1850 into a Free-State leader by 1855. The main thread that unites the statements in Moore’s broadside is his hatred of Benjamin F. Stringfellow and secessionism, a stance that undoubtedly embodied many Unionists’ viewpoints in the antebellum period.

Additional Resources

Reeves, Matthew. "Stringfellow, Benjamin Franklin." Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library.

Territorial Kansas Online, 1854-1861: A Virtual Repository for Territorial Kansas History. "H. Miles Moore, 1826-1909." Biographical sketch. Last modified September 12, 2013.

“Statement of Julia Mariata,” describing the abduction of H. Miles Moore by border ruffians at the American Hotel in Kansas City, Missouri. October 5, 1856. Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library.

See all documents related to H. Miles Moore.

See all documents related to Benjamin F. Stringfellow.