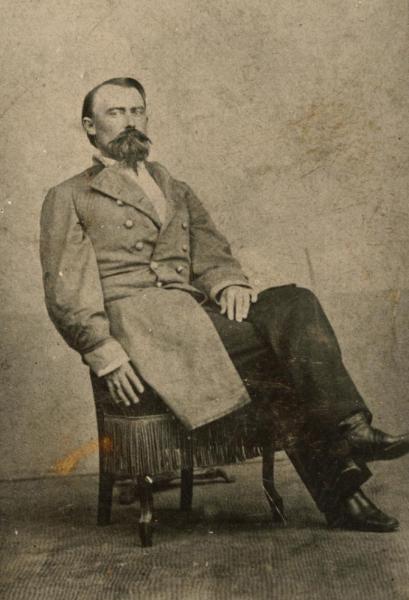

Major General Sterling Price. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

By Jason Roe, Kansas City Public Library

Each month in 2014, the Library will commemorate the sesquicentennial of the Civil War in Missouri and Kansas with a post derived from the thousands of primary sources that are digitized and incorporated into this website. The Library and its project partners collaborated to assemble this rich repository from the collections of 25 area archives, combining it with interpretive tools and original scholarship produced by nationally recognized historians.

Sterling Price Raises the "Army of Missouri"

On August 17, a man named E.P. Duncan wrote a letter from Desha County, in southeast Arkansas, to say that he was trying to return home, which was possibly in "western Missouri" where Duncan referenced having an "old friend." While other details surrounding the surviving letter are lost, and the letter cuts off abruptly, it happens to contain a first-hand account of events that presaged the largest Confederate cavalry raid of the Civil War and the longest cavalry raid in American history.

Duncan, who admitted to being in "feeble condition" and riding a mare that could not keep up with military horses, was attempting to make his way north to Missouri. But he discovered that Confederate Major General Sterling Price had issued orders preventing anyone from passing to the north of his army. Referencing rumors that had been circulating about an impending cavalry raid into Missouri, Duncan speculated that Price’s army was moving toward Missouri: "I passed [Price’s] pontoon bridges on the road to this place [Camden, Arkansas] on Sunday and all the army that I have passed is [going] that way."

Since the spring of 1864, rumors had indeed circulated that "Old Pap" Price, as his admiring soldiers called him, would invade Missouri with a force of unprecedented size in the West. Such a raid was not without precedent, as in the previous fall when General Joseph "Jo" Shelby led a "Great Raid" of 1,000 cavalrymen through southwestern and north-central Missouri, inflicting significant military and property losses. On August 4, 1864, Price finally received orders from Lieutenant-General Kirby Smith, the commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department, to "make immediate arrangements for a movement into Missouri, with the entire cavalry force of your district."

The military objectives of the proposed raid were outweighed by the political ones. By August 1864, the war was going poorly for the Confederacy, as Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia remained under siege at Petersburg, Virginia, and William Tecumseh Sherman’s invasion of Georgia pressed forward. In the West, however, Confederate leaders identified an opportunity to invade the state of Missouri, which seemed to be depleted of Union soldiers due to redeployments to the East in support of Grant and Sherman. If successful in capturing the primary target of St. Louis and, as a secondary target, the state capitol at Jefferson City, Price’s invading forces would install a Confederate state government, capture arms and supplies from the strategically located city on the Mississippi River, recruit secessionist Missourians into the flagging Confederate Army, and most ambitiously, perhaps even set up conditions for President Lincoln’s defeat in the upcoming November elections. If Lincoln were defeated, it was widely believed that a negotiated peace settlement with the Union would finally establish an independent Confederacy.

The lack of Northern resolve to continue the war was not entirely imagined. Although the strategic advantages held by the Union were finally starting to tip the balance against the South, the appalling 55,000 casualties suffered in Grant’s "Overland Campaign" (in May and June 1864), as well as similarly shocking losses in the Siege of Petersburg, dampened Northern morale. During that summer, historians widely agree that President Lincoln became convinced that he would lose his upcoming bid for reelection in November, which seemed likely to result in the election of a "Peace Democrat" who would end the war by recognizing the South’s secession.

Meanwhile, in Missouri, the Union Army still could not contain the guerrilla warfare conducted by the state’s pro-Confederate "bushwhackers." The violence between the two sides remained threatening and unpredictable enough that Alex M. Bedford, a Confederate soldier from northwest Missouri who was imprisoned in Delaware, wrote to his wife on August 2 that he was rejecting the possibility of parole because he considered it too dangerous to return home. For Price’s invading army, though, the number of bushwhackers presented an opportunity for much-needed recruitment. Quite optimistically, he speculated that as many as 30,000 recruits might be awaiting them in Missouri.

Despite ongoing personal feuds with other political and military leaders in the Confederacy, General Price—a former governor of Missouri, commander of some of the earliest secessionist forces at the beginning of the war, and wildly popular with his troops—was a natural choice to lead the invasion and recruitment efforts. In Arkansas during August 1864, he and his soon-to-be subordinate generals assembled a cavalry force that would, by mid-September, reach 12,000 men and 14 cannon organized into three divisions. Some 4,000 of these men were unarmed, but the plan was to acquire arms and ammunition as plunder of war. These were the troop movements and preparations that E.P. Duncan witnessed throughout August 1864.

On August 28, Price left Camden, and in the following day at Princeton he officially took command of two cavalry divisions of the District of Arkansas. On August 31, Price, along with Major General John S. Marmaduke and Major General James F. Fagan, departed Princeton for Pocahontas where they would add a third division under command of "Jo" Shelby. At the end of the month, no one knew what the outcome would be, but the Arkansas Confederates had set the scene for a truly momentous invasion.

Implementing the Draft in Missouri

On the Union side in Missouri, defensive preparations continued alongside the regular recruitment and drafting of soldiers. At the beginning of the Civil War, both sides optimistically hoped for a speedy resolution using relatively small numbers of volunteer soldiers, but when it became clear that the war would drag on, the Union and Confederacy both had to resort to conscription to fill their ranks. Far from being a smooth process, the draft for both sides suffered from complaints about unfairness, corruption, desertion, errors in implementation, and even riots such as in New York in July 1863. During August 1864 in northwestern Missouri, Captain William Fowler, the provost marshal for the 7th Congressional District, continued to implement the draft and field questions and complaints from his district’s residents.

Under most circumstances the male population of Missouri was subject to the Union Enrollment Act due to federal military control of the state, even though the Confederacy also claimed Missouri and recognized a secessionist state government that was exiled at the beginning of the war. Owing to its larger population and greater economic resources, the Union enacted its national draft nearly a year after the Confederacy in March 1863. The Enrollment Act required enrollment in the draft by all male citizens between the ages of 20 and 45 and similarly aged male immigrants who were filing for citizenship. The most contentious policy allowed draftees to pay $300 (a very large sum of money for typical farmers or factory workers of that time) to avoid service. Alternately, draftees could supply and often hired substitutes to take their place. Similar to Confederate grievances, Union citizens complained of the policy leading to a "rich man’s war" and a "poor man’s fight." By the end of the war, only about 2 percent of Union soldiers were conscripted, but an additional 6 percent were substitutes.

As provost marshal in northwestern Missouri, Captain William Fowler had to oversee the draft and the enlistment of volunteers. His surviving records provide significant insights into the behind-the-scenes work and frustrations that went into building and maintaining the Union Army at a local level. Fowler’s correspondence from August 1864 ranged from the mundane, such as answering requests to confirm the number of volunteer enlistment quotas for individual counties, to the concerned or outraged. On August 4, the sheriff of Holt County, William Kaucher, wrote to Fowler asking him to confirm whether he should enlist 158 volunteers. The letter referenced the quota system, which applied to each county based on population. Kaucher also sought to confirm that the county received credit for recruits supplied to the 9th Missouri State Militia. If an inadequate number of men volunteered to meet the quotas, the draft would be implemented in the affected communities to make up the difference.

Read the full military correspondence of Captain William Fowler.

Fowler frequently received reports of omissions or other errors that needed to be investigated. James Beatty, deputy provost marshal for the 20th Missouri subdistrict, forwarded a complaint from William Griffith, a resident of Taylor, Missouri, who complained that his township was "entitled to many more credits for soldiers furnished." Beatty’s reply, which he reported to Fowler, was surprisingly nonchalant: "I thought if there was any thing wrong in that respect it was owing to carelessness or neglect of the enrolling officer, and that perhaps it was now too late to rectify any such mistake." Beatty did at least forward the list of names that Griffith supplied, but the existing records do not contain Fowler’s response, if there was one.

Unique issues came to Fowler’s desk in different months. In March 1864 an enrolling officer named John Young reported to Fowler that the draft lists contained duplicates of the names of James Redding, John Redding, Nathaniel Crow, and Moses Seabolt. Young notified Fowler of the duplication, "for fear of subjecting them to a second ordeal in the draft." In the previous year, Fowler received orders stating that Confederate Army deserters who were drafted were to be exempted from combat roles against the Confederates and either given support duties or dismissed from service altogether. Two days later, a second order confirmed that Fowler should not include the names of men known to be "in the Rebel service" for the draft. The ages of other young men were either mistakenly listed for the draft, or else they claimed to be younger than 19. In one such case, two "boys" from Atchison County sought an exemption from military duty but could only offer affidavits from their parents as proof of their age.

The poor record-keeping of the era ensured that any decisions made by Captain Fowler must have been plagued by uncertainty. Fowler’s correspondence from August 1864 and throughout the war gives modern readers an inside view of the bureaucracy that was necessary to maintain military recruitment on a day-to-day basis. Almost all of it was written out by hand and subject to limited oversight, poorly defined procedures, limited information about draftees, personal bias, and careless errors, making it difficult to administer fairly. But with rampant guerrilla warfare and an army gathering in Arkansas, Missouri’s enrolling officers forged ahead with the draft.

Kansas City’s Mayor Runs for Congress

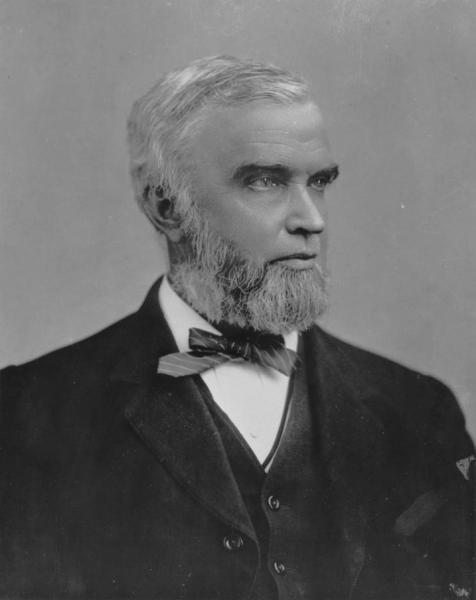

Another man who persevered was Robert T. Van Horn, the mayor of Kansas City and a colonel in the Union Army who had been mustered out of military service at the beginning of 1864 despite a commendable record that dated back to 1861 when he was credited with keeping Kansas City under Union control. In August 1864, after more than half a year of searching for a new position in support of the Union cause, a path finally opened for Van Horn to run for office in the U.S. House of Representatives.

In March of the same year, Senator and Brigadier General John Brooks Henderson (also from Missouri) had written to Van Horn with sympathy toward his dismissal and vowed to secure him a new appointment. In April, Henderson wrote again to say that he had been lobbying President Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton to secure Van Horn an appointment as a brigade commander. According to Henderson, Stanton "refused to authorize you [Van Horn] to raise a brigade." Henderson continued to complain that, "If Lincoln consents to appoint, some secretary interferes and he caves.... If I can get you a good appointment, I will get it."

It is entirely possible that Stanton, who had a well-established reputation for attacking Union officers with alleged Southern sympathies, disapproved of Van Horn’s background. At the outset of the war, Van Horn had been a Democrat and the newspaper he owned, The Kansas City Daily Western Journal of Commerce, had shown a slight proclivity for supporting the proslavery side during the "Bleeding Kansas" era.

Van Horn’s prewar stance on the issue of slavery remains unclear, however, as his prewar editorials generally ignored the possibility of war and focused instead on commercial issues and the need for peaceful conditions to promote the economic development of Kansas City. Still, after switching to the Republican Party and becoming a well-respected leader in the party, and after three years of supporting the Union war effort and even being captured in a battle, Van Horn’s credentials as a Unionist and supporter of the Lincoln administration should have been self-evident.

Senator Henderson’s efforts and Van Horn’s record notwithstanding, his promotion to brigadier general never came to pass, but another opportunity opened up for Van Horn in August 1864. The next surviving letter from Senator Henderson, dated August 31, 1864, contained a surprise twist of fortune. Although Van Horn would not be appointed a general, Henderson wrote,

By the bye, the Pres’t has taken up the most unaccountable liking to you. I told him I wanted him to appoint you Tax [Commissioner] at once. He said he [didn’t] want to send you out of the District, that you [didn’t] want any such office, that you must run for Congress in your district & be elected.

Henderson added that President Lincoln was disappointed in the recommendations and "requests" of the current representative of the Missouri 6th Congressional District, Austin A. King. Lincoln apparently told Henderson that King "ought to be beaten," and Henderson offered to give Van Horn whatever support he needed to secure his party’s nomination and run for office.

It is unclear when Van Horn started actively running for Congress, but on the same day that he received the letter from Henderson, Colonel Andrew G. Newgent, from Cass County, Missouri, issued a campaign circular outlining five reasons why Van Horn should be nominated and elected to represent the Missouri 6th Congressional District. Among the reasons provided were Van Horn’s longstanding residence in and knowledge of Missouri, his actions against the secessionists in 1861, his participation in battles or skirmishes, and his demonstrated competence as a state senator in the Missouri legislature. Newgent’s fifth reason for electing Van Horn was that he believed that Cass County could deliver 500 more votes for him than for any other candidate.

Learn more about the Hannibal Bridge and the establishment of the Kansas City Stockyards from an exhibit at the Kansas City Public Library.

Van Horn’s eventual nomination and election to the U.S. House of Representatives in November proved to be auspicious for his favorite city. Serving for three terms in Congress, he worked to promote the construction of a bridge by the Hannibal & St. Joseph Railroad that would cross the Missouri River at Kansas City rather than at a rival city such as Leavenworth, Kansas. His efforts, along with those of several local railroad boosters, resulted in Congress legally authorizing the construction of the Hannibal Bridge, which spanned the Missouri River at Kansas City in 1869 and spurred the city’s stockyards industry and commercial growth into the 20th century. In some respects, then, Kansas City’s historical growth from a rugged frontier town into a major Midwestern city dated back to August 1864, when the circumstances of the Civil War led Robert Van Horn to run for Congress.