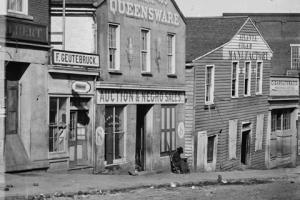

A slave market in Atlanta, Georgia. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

By Jason Roe, Kansas City Public Library

Each month in 2014, the Library will commemorate the sesquicentennial of the Civil War in Missouri and Kansas with a post derived from the thousands of primary sources that are digitized and incorporated into this website. The Library and its project partners collaborated to assemble this rich repository from the collections of 25 area archives, combining it with interpretive tools and original scholarship produced by nationally recognized historians.

Auction of Slaves and Other Property

A constant of life is the need to settle estates or distribute inheritances upon the death of a parent. Complicating matters in the case of deceased Chariton County resident John C. Cavanagh, whose estate was being settled in April 1864, was that a significant portion of his property consisted of human beings. This indenture, or legal document outlining how Cavanagh’s property would be distributed to heirs, describes his property holdings as a total of 256 acres of land, a 24-year-old man named Abe, a 27-year-old woman named Lucy, and a 5-year-old girl named Eliza.

By early 1864 the institution of slavery was already in decline in Northern border states and across significant portions of the South, but the indenture shows that the ownership and sale of slaves still occurred in border states, including Missouri. President Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation more than a year before, but it only legally freed slaves in rebellious states where the Union did not necessarily have control. Cavanagh held his slaves in Chariton County, which was in the heart of Missouri’s “Little Dixie” region that was largely populated by Southern migrants, their descendants, and an enslaved portion of the population two to five times higher than the average for the rest of the state. The fate of the slaves Abe, Lucy, and Eliza following the death of their master would be determined by Cavanagh’s heirs and the legal system.

According to the document, John Cavanagh was survived by five children younger than the age of 21: David L., William, Jane, Sarah, and Alphonso. David and William were left with one legal guardian with the last name of Cavanagh, while the other three children were left with a separate guardian. The guardians petitioned the court of Chariton County to sell the real estate and slaves at auction, so that the estate could be divided equally among the five surviving children. The court ordered the county sheriff to “proceed to sell said real estate and slaves ... to the highest bidder before the court house door in the town of Keytesville....”

Of course no mention was made of the outcome for Abe, Lucy, and Eliza. There is nothing to indicate whether the 5-year-old Eliza might have been Abe and Lucy’s daughter or to stipulate that they be kept together in the sale. They would simply be sold as any other property, and today all we know about them are their names and approximate ages.

Missouri’s slaves who could not serve in the Union military to earn their freedom, or who were not otherwise set free by their masters, had to wait until January 11, 1865, for emancipation. The 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution finally freed all slaves nationally after its ratification on December 6, 1865.

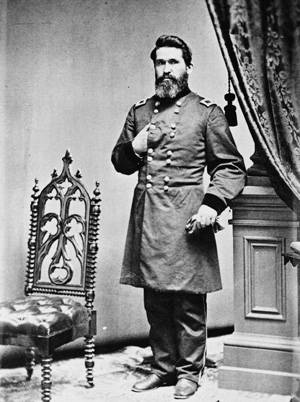

General Blunt Removed from Command

As the grip of winter eased in April 1864, military actions resumed, but the noted Union General James Gillpatrick Blunt found himself removed from command and sitting on the sidelines as of April 18. A bound letterbook, containing correspondence of the Kansas Colored Volunteers, records that Blunt wrote to Major C.W. Foster in Washington, D.C., to inform him that he was being removed from command of the Kansas Division and had turned over recruiting responsibilities to Lieutenant Colonel Fred W. Schaurte.

Blunt’s fall from grace over the previous months must have been a surprise to those who knew him well. Prior to the Civil War, he had gained fame as a physician, an abolitionist and Underground Railroad supporter, and a “jayhawking” militiaman alongside James H. Lane and John Brown. After several victories early in the war, he rose to become the first and (during the Civil War) only major general from the state of Kansas on November 29, 1862. Blunt commanded the Department of Kansas and, following a military reorganization, the “Kansas Division” of the Army of the Frontier. In these posts he won several strategic victories in southern Kansas, Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), and Arkansas before suffering an ignoble defeat on October 6, 1863.

Blunt’s defeat came on October 6, 1863, at the hands of the Missouri guerrilla leader William Clarke Quantrill, who, less than two months before, had led his “Raiders” in an assault on the town of Lawrence, Kansas and killed between 160 and 190 men and boys. Quantrill’s Raiders fled back to Cass County, Missouri, immediately after the raid, but in October he returned to Kansas with approximately 400 men to threaten the earth-and-log Fort Blair, near Baxter Springs in the southeast part of the state. Blunt, who had personally ordered the construction of the fort the previous May, attempted to intercept Quantrill’s men but briefly mistook the guerrillas for Union soldiers due to the blue coats they wore. Blunt barely escaped with his life, nearly 100 of his soldiers were killed, and the retreating federals had to burn the fort to keep it from falling into enemy hands.

It was against this backdrop that Blunt lost his command in April 1864, and he would have to wait until later in the year to redeem himself by helping to repulse a great cavalry raid led by Major General Sterling Price. Even after that victory, and years after the war, Blunt would eventually be committed to an insane asylum, where he died of “softening of the brain.” In the meantime, though, he was reassigned to the remote post of Fort Riley, Kansas, to await a new command.

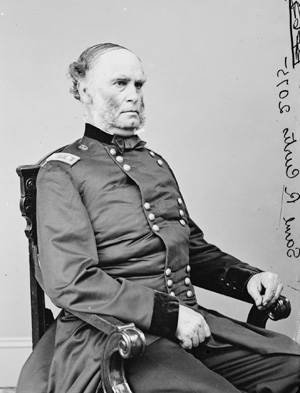

General Curtis Pursues Quantrill’s Raiders

General Blunt’s defeat at Fort Blair in October 1863 had even deeper repercussions for another Union leader, Major General Samuel R. Curtis: his own son, Major Henry Zarah Curtis, was killed in the ambush. While Blunt was being reassigned to Fort Riley in April 1864, Curtis was supporting the efforts of Colonel W.A. Phillips, whose Indian Brigade was pursuing Quantrill’s men in Indian Territory and southern Kansas. A telegram sent to Kansas Governor Thomas Carney on April 26, 1864, forwarded the communications between Phillips and Curtis.

Phillips reported to Curtis, who was then best known for his victory at Pea Ridge, Arkansas, early in the war, that his troops were pursuing Quantrill and included some details about crossing the Verdigris and Arkansas Rivers, as well as about the considerable rain that had fallen over the previous two days. The Indian Home Guard, of which Phillips’s brigade was a part, was made up of members of the “Five Civilized Tribes” (the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole), who had broken away from their leaders’ treaties with the Confederacy and instead joined the Union Army.

Despite Phillips’s conclusion that some of his men might intercept Quantrill soon, he and Curtis were on an elusive quest. Aside from being notorious for their guerrilla tactics and eluding Union forces, Quantrill’s Raiders were never formally inducted into the Confederate military, struggled to maintain a command structure, and did not remain a unified force following the raid on Lawrence and the battle at Fort Blair. Quantrill’s Raiders broke up that winter and spring, with George Todd and William “Bloody Bill” Anderson leading guerrillas back into Missouri and Quantrill taking some men to Kentucky later in the year.

The enigmatic Quantrill may not have been anywhere near the Arkansas River in April 1864, and we know that Curtis never had the opportunity to avenge his son’s death, if he desired such an outcome. Quantrill would not, however, survive the war. In May 1865 he was shot in the spine in a federal ambush near Taylorsville, Kentucky, and died several weeks later.